|

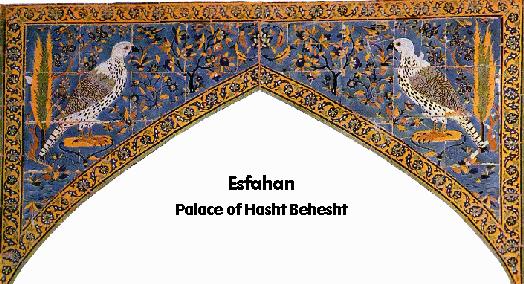

Achaemenian

glazed tile

|

Zoroaster's

Ka-ba at Naqsh-e Rostam, Marvdasht

|

|

Head

of Tepti Ahar's statue

|

Taq-e

Bostan, Coronation of Ardeshir II Sassani

|

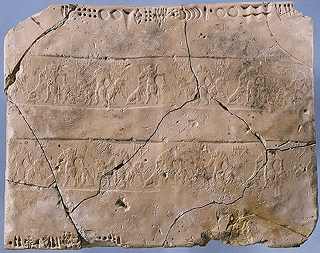

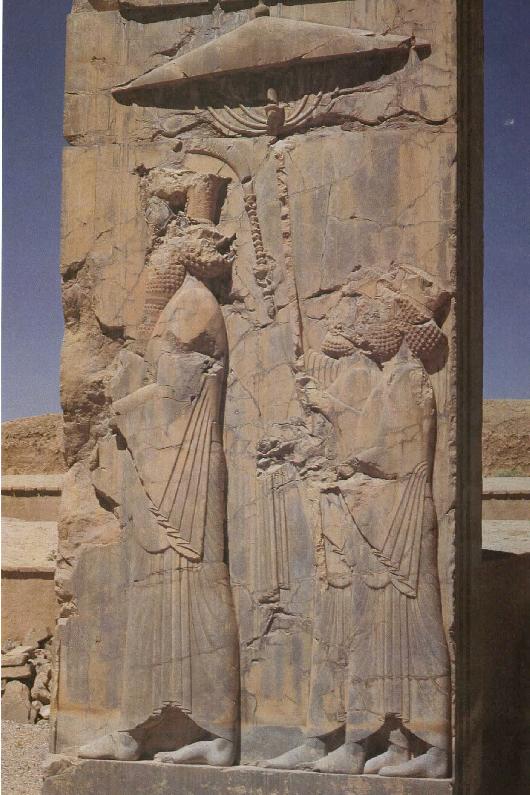

Stele

of Artaxerxes

|

Taq-e

Bostan, Khosrow Parviz on horseback

|

|

Head

of Achaemenian soldier, Persopolis

|

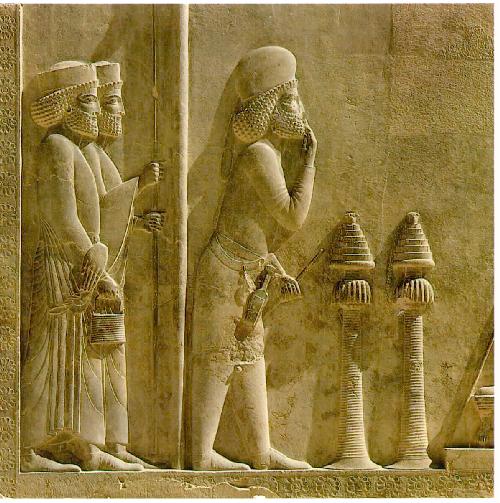

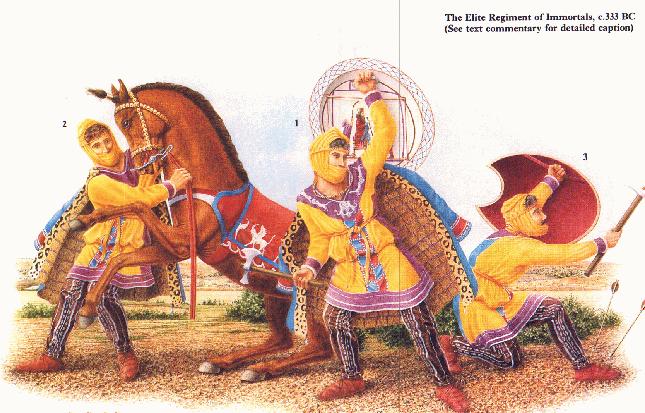

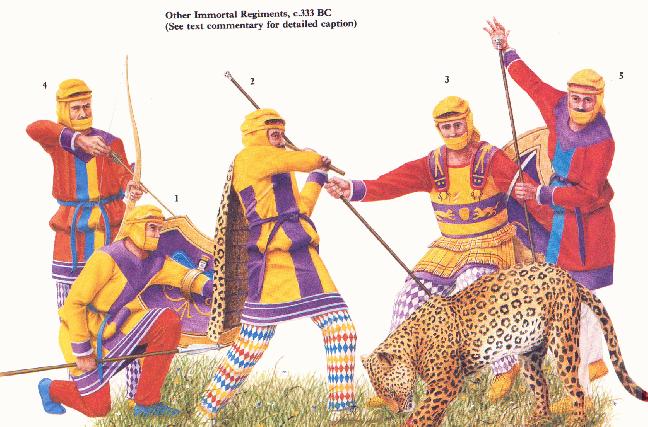

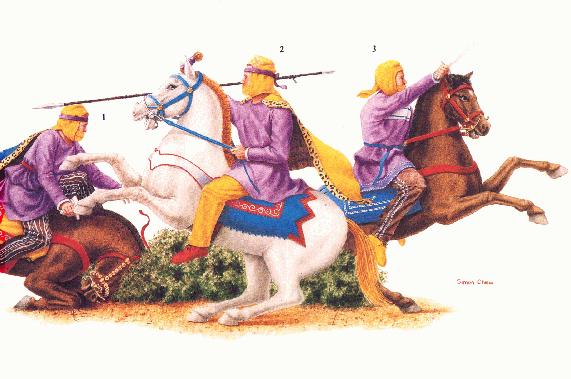

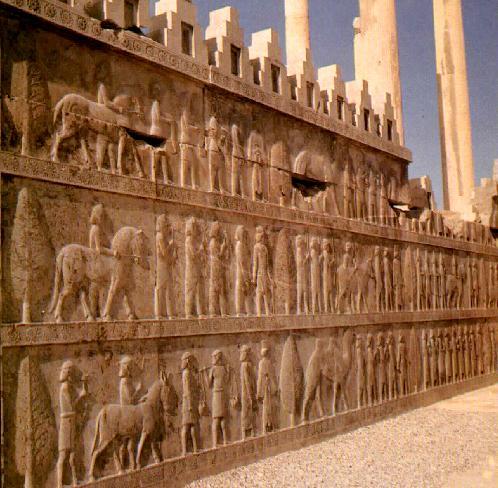

Rows

of "Immortals" on northern side of stairway,

Persepolis

|

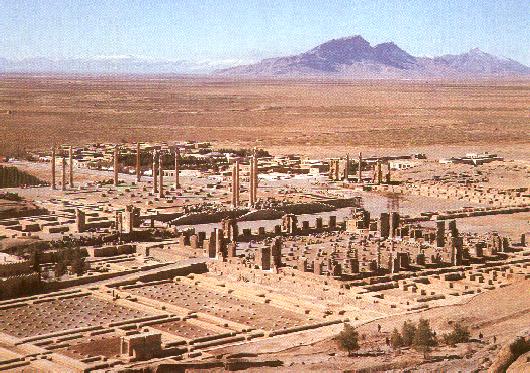

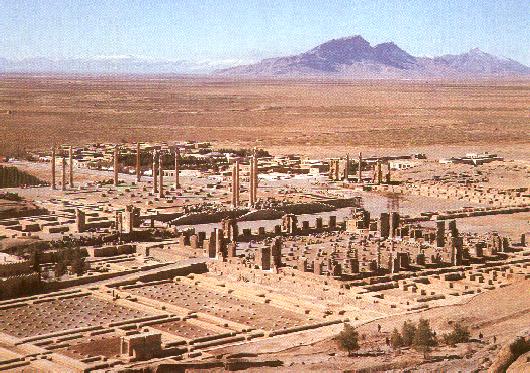

Panorama

of Persepolis from the top of Mt. Rahmat

|

Tachar

Palace or Mirror Hall, built under Darius the Great

|

Persepolis

|

Persepolis,

Portico

|

Palace

of Cyrus, covering 2,620 sq. meters

|

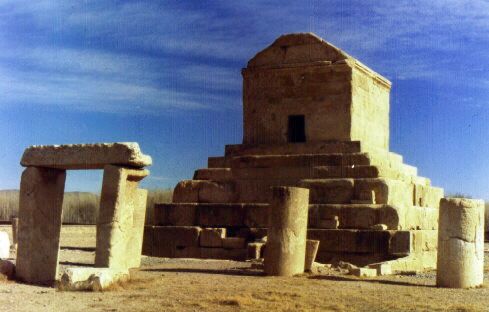

Pasargad,

Tomb of Cyrus

|

Bull-shaped

capital. Persepolis. Achaemenian period

|

Bull

& Lion, eastern stairway of the Apadana at Persopolis

|

Gold-beaten

silver pitcher, 7th century AD

|

Head

of an Achaemenian price, 5th Century BC

|

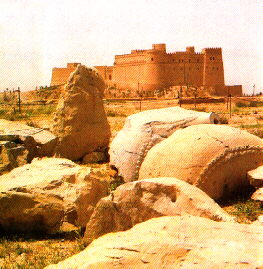

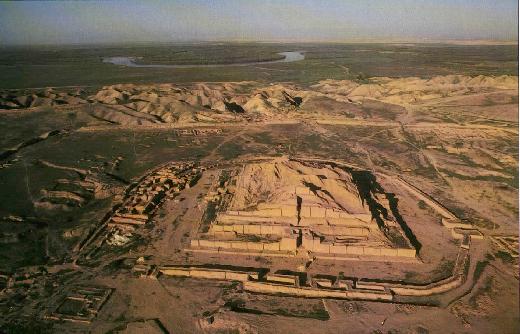

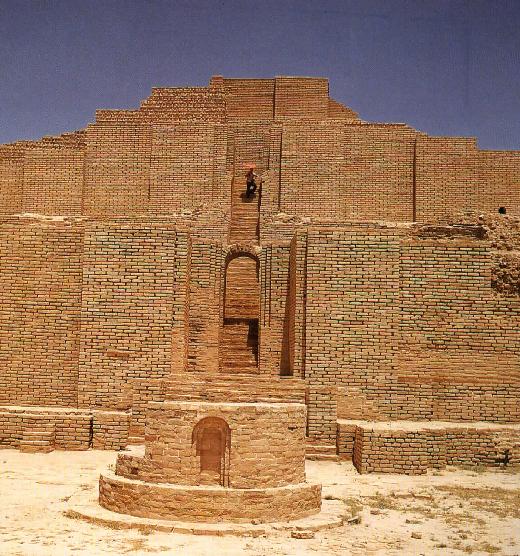

Elamite

temple in the city of Dur-Untash. Mid- 12th century BC

|

Citadel

of Shoosh

|

Golden

four-horsed war chariot. 6th to 4th Century BC

|

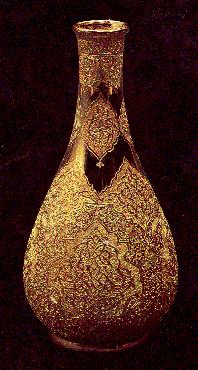

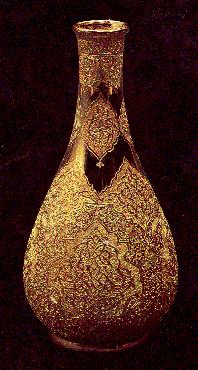

Incised

glass vase, Arsacid period. Azarbaijan region

|

Twin-shelled

ceramic ewer, 6th century AD. Gonabad region

|

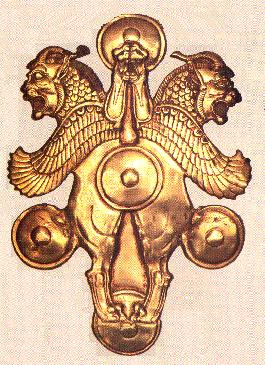

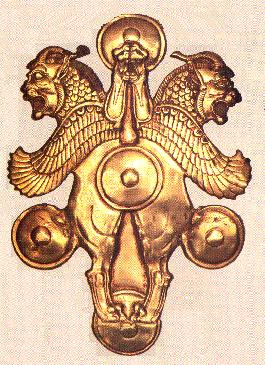

Golden

lion head, garment decoration

|

Golden

ring of power

|

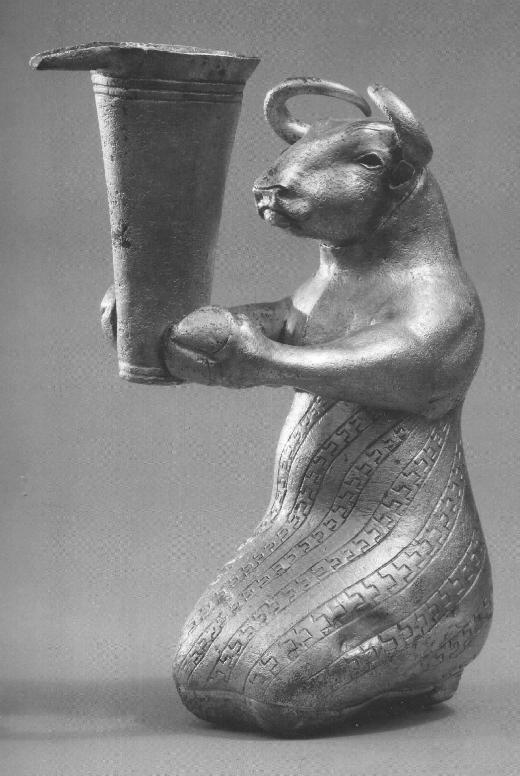

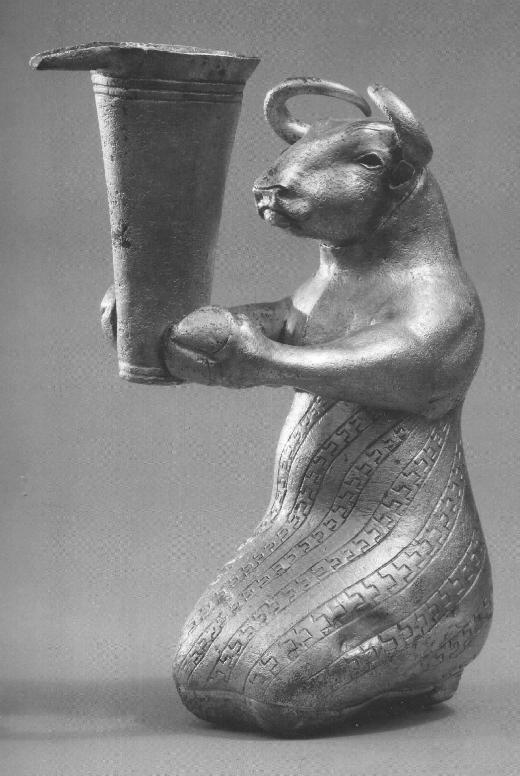

Golden

rhyton, 5th century BC, Hamadan

|

Helmet

|

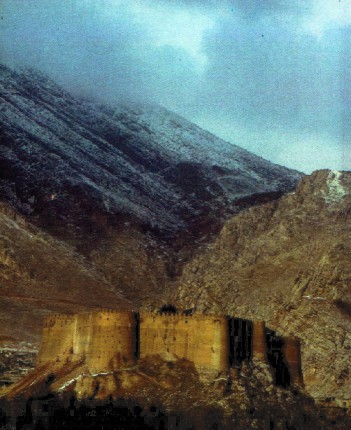

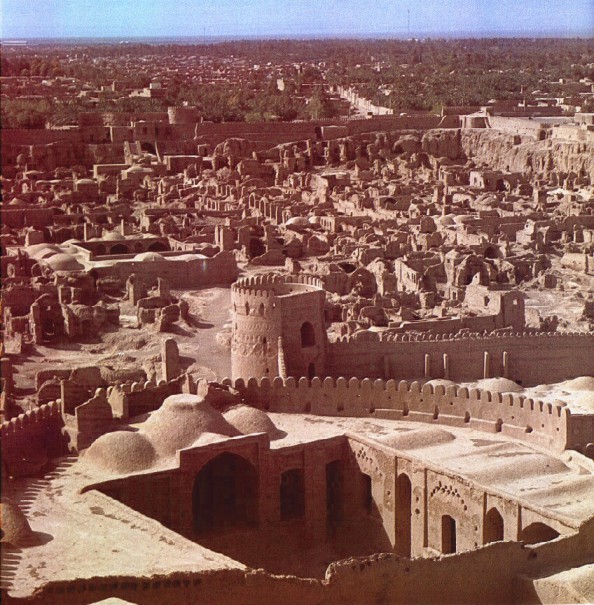

Arg-e

(citadel of) Bam, close to Kerman

|

|

Interesting Places |

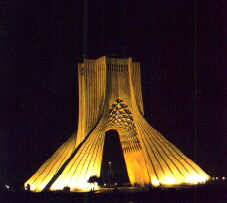

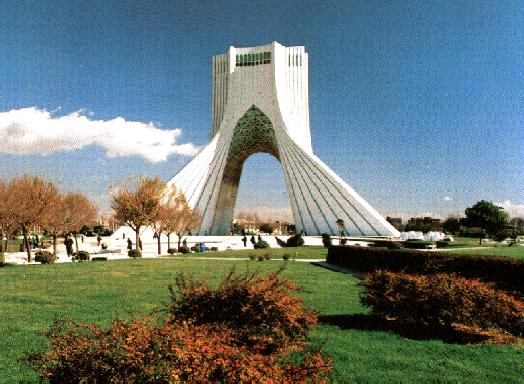

Azadi

(Shahyad) Square

|

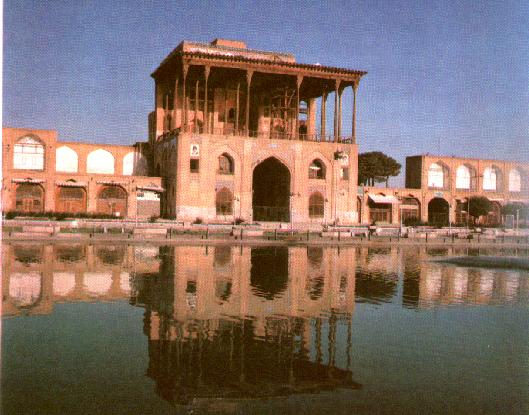

Ali-Qapu

Palace

|

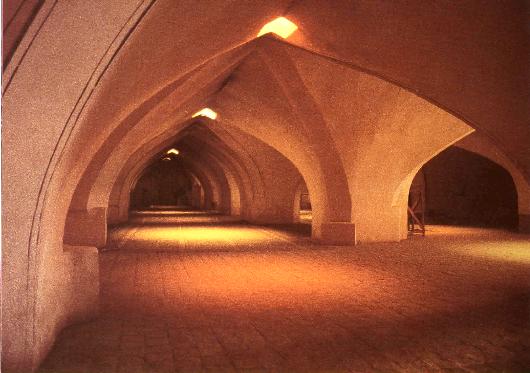

Vakil

Bath-house, Kerman

|

Cheshmeh

Ali Monument in Damghan, Qajar period

|

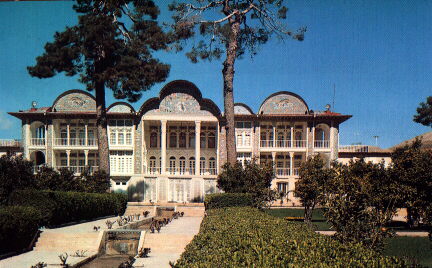

Narenjestan

(orange orchard) of Qavam, Shiraz

|

Chehel-Sotun

Building in Qazvin, Qajar period

|

Chehel-Sotun

Building in Qazvin, Qajar period

|

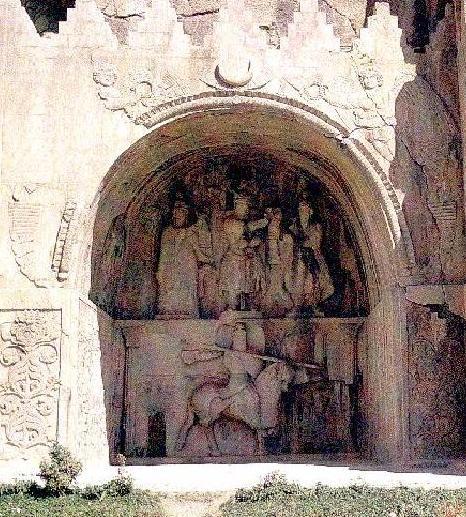

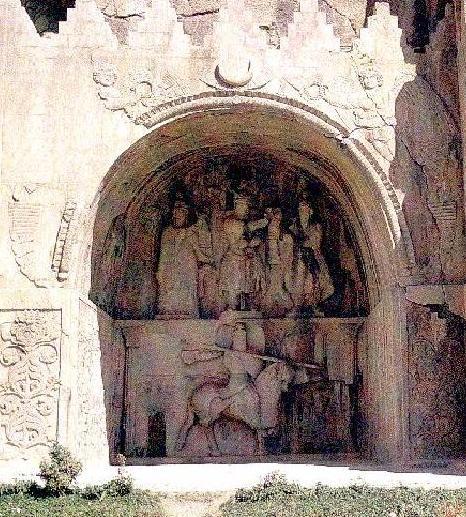

Taq-e

Bostan, Kermanshah, Sassan period

|

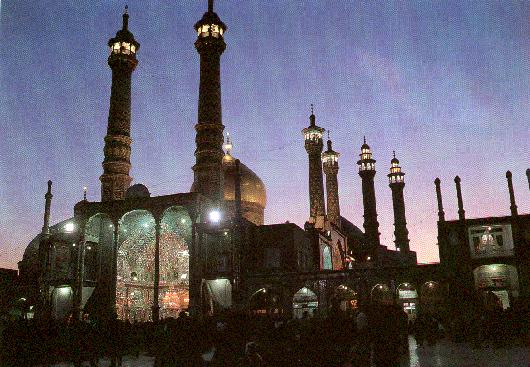

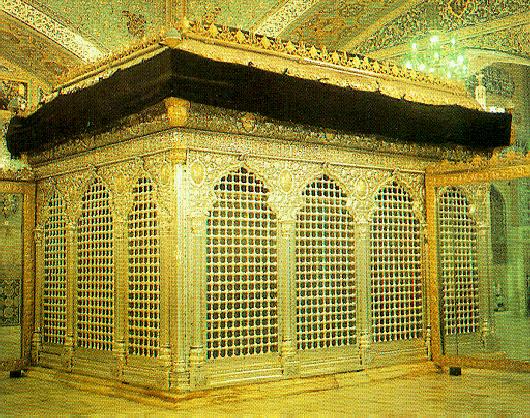

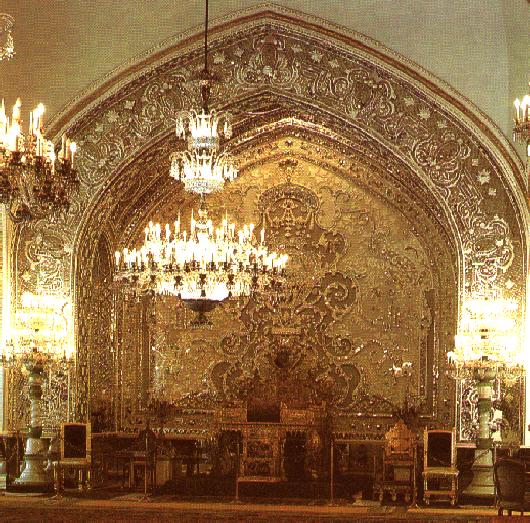

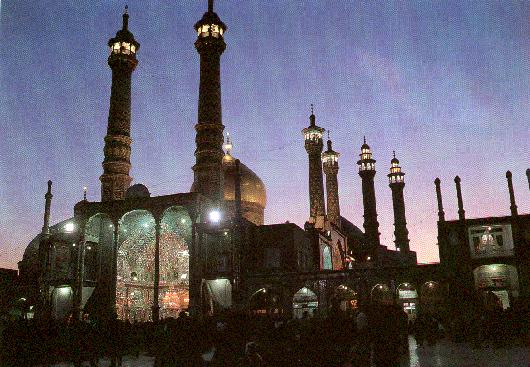

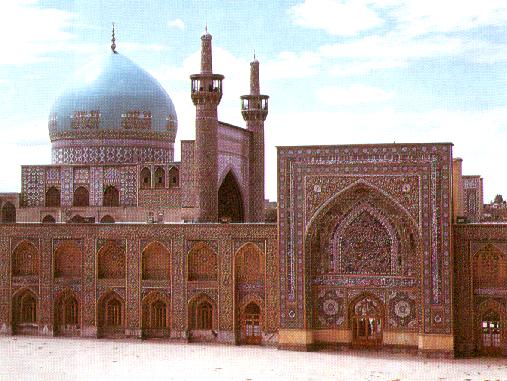

Holy

Shrine of Imam Reza, Mashhad

|

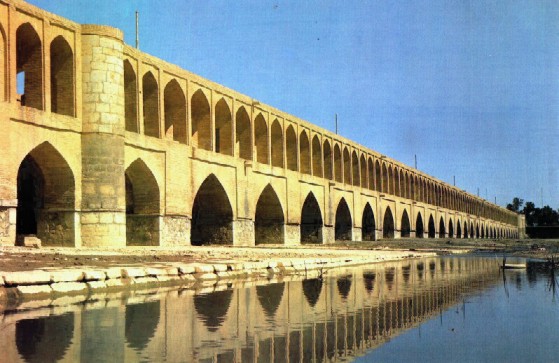

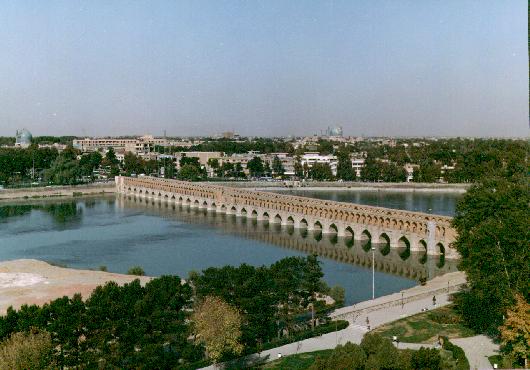

Khaju

bridge, Esfahan

|

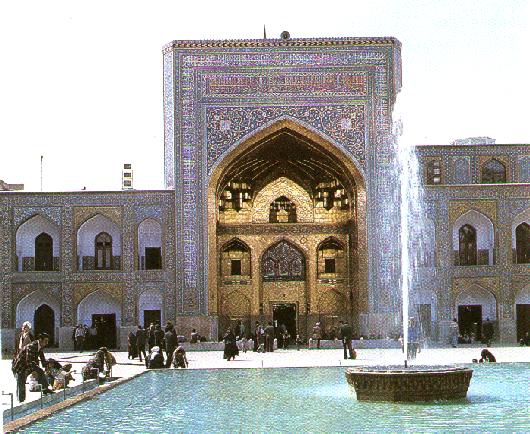

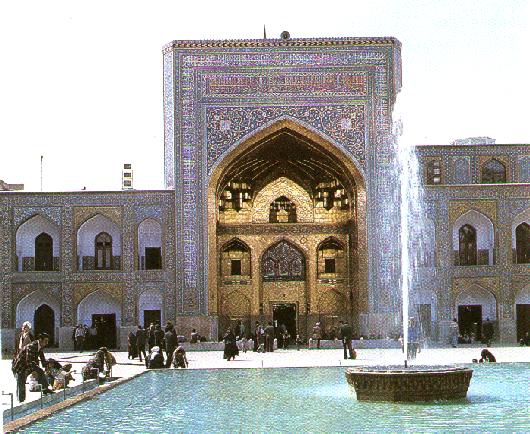

Emam

(Shah) Mosque of Esfahan

|

Abarquh,

old house with two-tiered wind-towers. 13th century AD

|

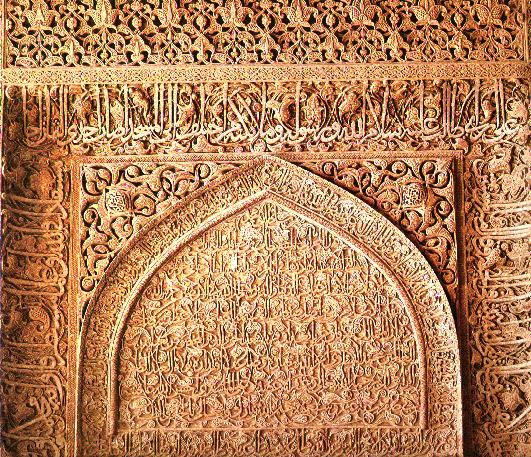

Jame

(Congregational) Mosque of Esfahan

|

Madrasa

(theological school) of Khargerd, Timurid period

|

Emam

(Shah) Mosque of Esfahan, tessellated tile-work

|

Emam

(Shah) Mosque of Esfahan, Safavid period

|

Ali

Mosque, Esfahan. Brick and tile-wrok

|

Chahar-Bagh

(Shah's Mother) Madrasa in Esfahahn

|

Tachar

Palace, Persepolis

|

Mausoleum

of the Ilkhanid ruler Oljaitu at Soltaniyeh, Zanjan

|

Iran-e

Bastan Museum

|

Avan

Lake, between Roodbar and Alamut

|

Massule

|

Coronation

Gallery

|

Bagh-e

Eram, Shiraz. Built by Nasser-ed-Din Shah

|

Shah's

Crown, 3380 diamonds, 638 pearls, 5 emeralds & 2 sapphires

|

Empress'

Crown, 105-ct emrld, 1469 dmnds, 36 emrlds, 36 rubies & 105 pearls

|

The

Darya-ye Noor, 182-carat diamond

|

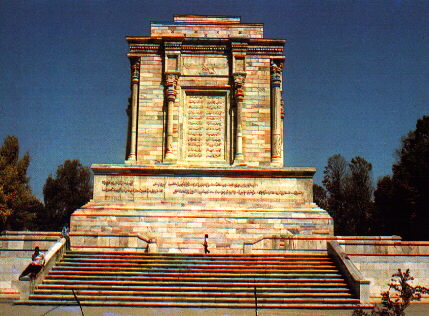

Tus

Museum, Tomb of Ferdowsi

|

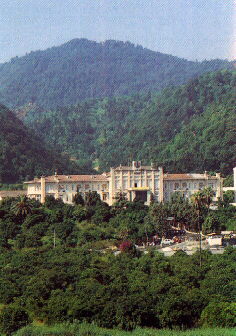

Ramsar

Palace, Presently Ramsar Hotel

|

|

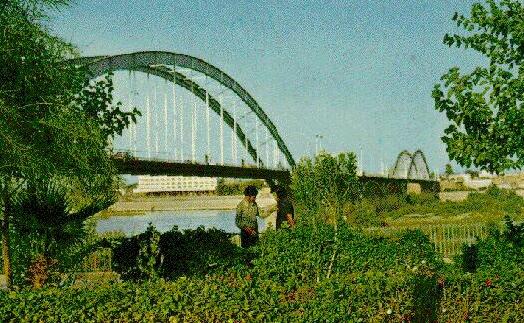

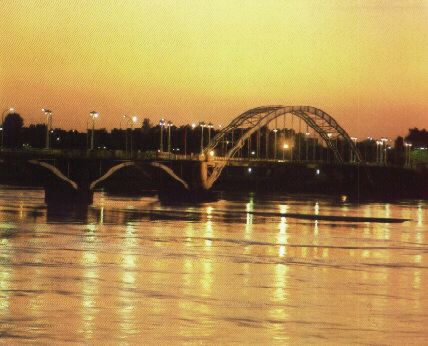

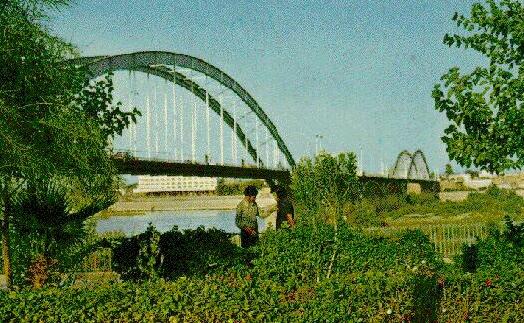

Ahwaz showing Bridge over the

Karoon

|

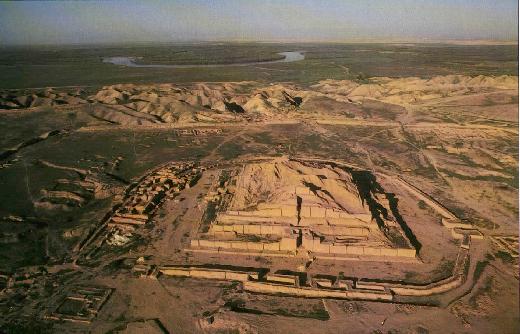

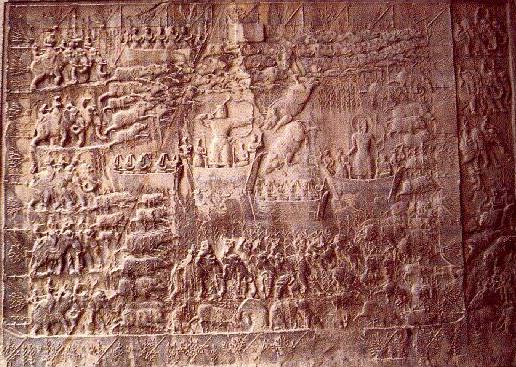

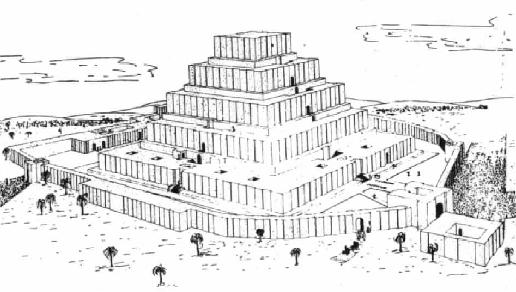

Site of King Untash Napirisha's

Ziggurat, Chogha Zanbil,

25 miles south-east of Susa, c 1250 BC

|

| |

|

|

Famous Persian |

|

Avicenna.

Hojjat-ol-Haqq Sheikh-or- Raeis Sharafol-Molk Abu-Ali Hossein ebn-e

Abdollah ebn-e Sina, was a physician & savant of the 4th century

AD. Avicenna's two most important works are The Book of Healing and

The Canon of Medicine. The first is a scientific encyclopedia covering

logic, natural sciences, psychology, geometry, astronomy, arithmetic and

music. The second is the most famous single book in the history of

medicine.

|

|

Attar

Neishaburi. Farid-ed-Din

Abu-Hamed ebn-e Abu-Bakr Ebrahim-al-Haqq Attar Kadkani Neishaburi is a

poet of the 6th-7th century AD.

|

|

Ferdowsi.

Abolqassem Mansur ebn-e Hassan Ferdowsi Tussi is the greatest Iranian epic

poet. The author of the Persian national epic, Shah-nameh

("Book of Kings"). Ferdowsi was occupied by this task for

35 years. Written for Sultan Mahmud of Ghazna, the Shahnameh

is a poem of nearly 60,000 verses, mainly based on the Khvatay- namak,

a history of the kings of Persia in Pahlavi (Middle Persian) from mythical

times down to the 7th century.

|

|

Rudaki.

Abu Abdollah Jafar ebn-e Mohammad is the first poet of note to compose

poems in the "New Persian," written in Arabic alphabet, widely

regarded as the father of Persian poetry. Approximately 100,000

couplets are attributed to him, but of that enormous output, fewer than

1,000 have survived. His poems are written in a simple style,

characterized by optimism and charm and, toward the end of his life, by a

touching melancholy.

|

|

Shahryar.

Shahriar is a great contemporary Iranian poet.

|

|

Khayyam.

Abu al-Fath Omar ben Ibrahim al-Khayyam was a poet as well as a

mathematician and astronomer of the 11th century. He discovered a

geometrical method to solve cubic equations by intersecting a parabola

with a circle. Despite his great scientific work, Khayyam is best

known as a result of Edward Fitzgerald's popular translation in 1859 of

nearly 600 short four line poems the Rubaiyat .

|

|

Zakaria-ye-Razi.

Mohammad ebn-e Zakaria-ye Razi of the 3rd century AD is a celebrated

alchemist and Muslim philosopher who is also considered to have been the

greatest physician of the Islamic world. His experiments led to the

discovery of sulfuric acid and alcohol. His two most significant medical

works are the Kitab al-Mansuri and Kitab al-hawi.

|

|

Vahshi

Bafqi. Mowlana Shams-ed-Din (Kamal-ol-Molk)

Mohammad Vahshi Bafqi is a poet of the 10th century AD.

|

|

Khajeh

Abdollah Ansari. Khajeh Abdollah

Ansari Heravi lived in the 4th and 5th centuries AD.

|

|

Nasser-Khosrow

Qobadiani. Hakim Abu-Moeen Nasser-Khosrow

ebn-e Haress al-Qobadiani al-Balkhi al-Marvazi is a poet and writer of the

5th century AD.

|

|

Mohtashem

Kashani. Shams-osh-Shoara

Kamal-ed-Din Mohtashem Kashani is a poet of the 10th century AH. He is

famous for his religious poems.

|

|

Sa’di.

Abu Mohammad Moshref-ed-Din Mosleh ebn-e Abdollah ebn-e Moshref as-Sadi

Shirazi is a great poet of the 7th century AD. His best known works

are the Bustan (1257; The Orchard, 1882) and the Gulistan

(1258; The Rose Garden, 1964). The Bustan is entirely in

verse (epic metre) and consists of stories aptly illustrating the standard

virtues recommended to Muslims. The Gulistan is mainly in prose and

contains stories and personal anecdotes.

|

|

Kamal-ol-Molk.

The great Iranian painter Mohammad Ghaffari, entitled Kamalol-Molk, lived

in the 13th and early 14th century AD.

|

| |

Hafiz

(1325?-1389?), Persian poet, born in Shìraz (now in Iran) into a poor

family. Originally named Mohammed Shams od-Din, he gained the respectful

title Hafiz, meaning “one who has memorized the Koran,” as a teacher

of the Koran. He was a member of the order of Sufi mystics and also, at

times, a court poet. On a deep level, according to some scholars, his

poems reflect his consuming devotion as a Sufi to union with the divine.

They also satirize hypocritical Muslim religious leaders. Hafiz's

work, collected under the title of Divan (trans. 1891), contains more than

500 poems, most of them in the form of a ghazal, a short traditional

Persian form that he perfected. The extraordinary popularity of Hafez's

poetry in all Persian-speaking lands stems from his simple and often

colloquial though musical language, free from artificial virtuosity, and

his unaffected use of homely images and proverbial expressions.

|

| |

|

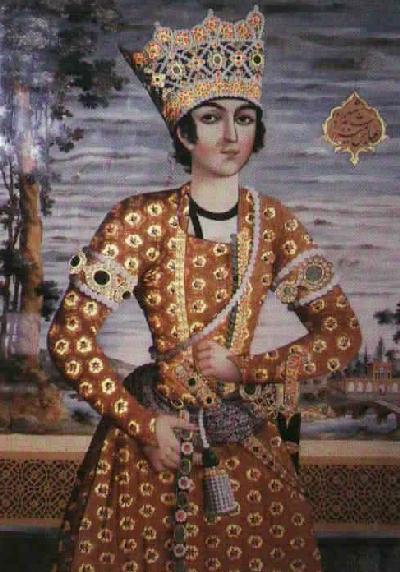

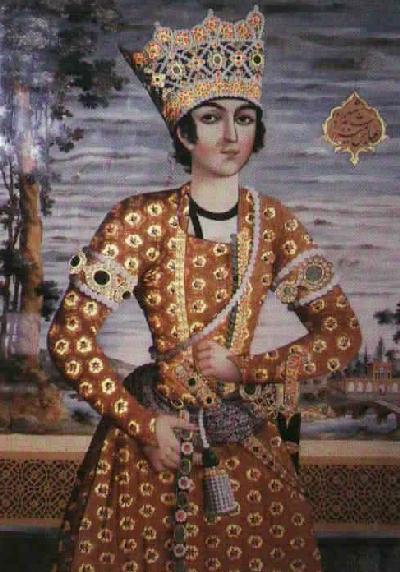

Prince

Abbas Mirza, eglomise.

Ethnographical Museum

Tehran

|

|

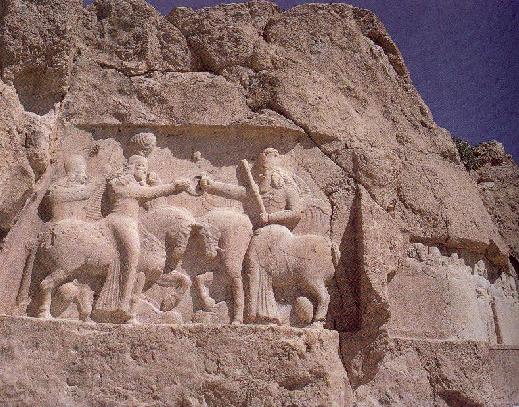

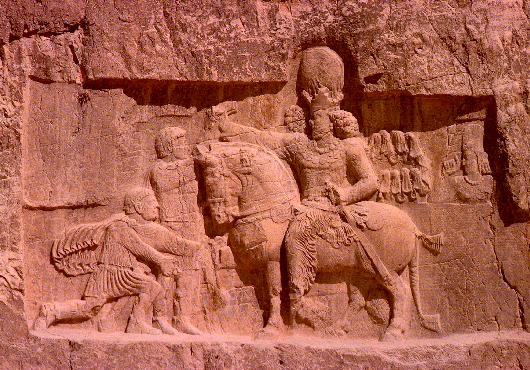

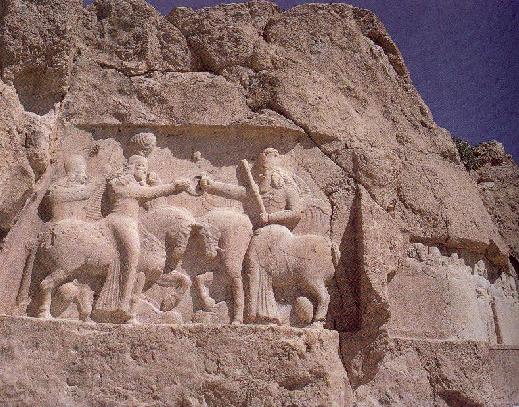

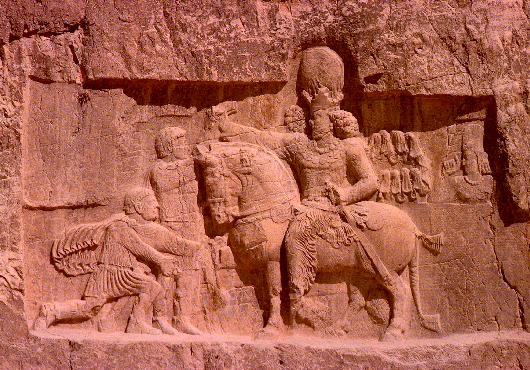

Nagsh-e Rostam (Nagsh-i Rostam)

close to Persepolis is actually the site where the Achaemenid kings

put up the reliefs and their tombs. The Sassanian kings however added

some reliefs of their own here. This relief shows the Investiture of

Ardeshir I (on left ) 224-41 AD, the first Sassanian King of Persia.

|

|

Close

up of a Bas Relief of Cyrus by Lewis Batros

at Bicenntenial Park, Sydney, Australia.

The

Original is at Pasargade, the city Cyrus built as his capital in Fars,

Iran.

If

you wait a bit the image will alternate between the original relief at

Pasargade and the replica in

|

|

.

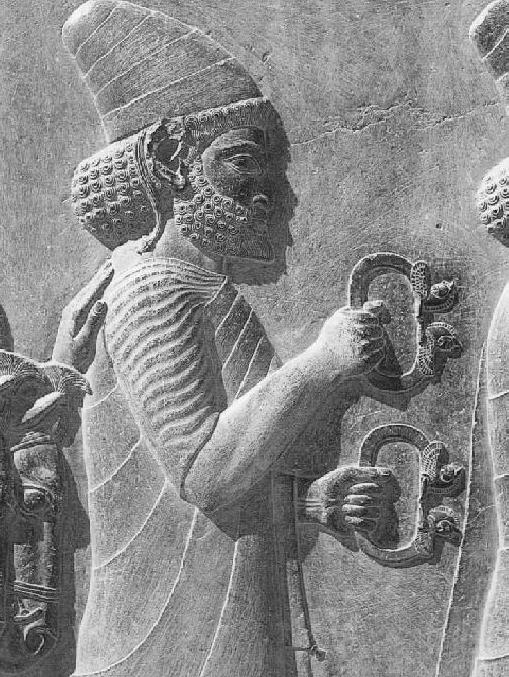

Darius

the Great

(521-486 BC)

Enthroned

in Peresepolis, the magnificent city that he built, Darius I firmly

grasps the royal scepter in his right hand. In the left, he is holding a

lotus blossom with two buds, the symbol of royalty.

This

Bas-relief is at the Apadana Palace, Persepolis, showing Darius

receiving Iranian delegates at audiance during the New Year (Nowrouz,

March 21st) festivities.

|

|

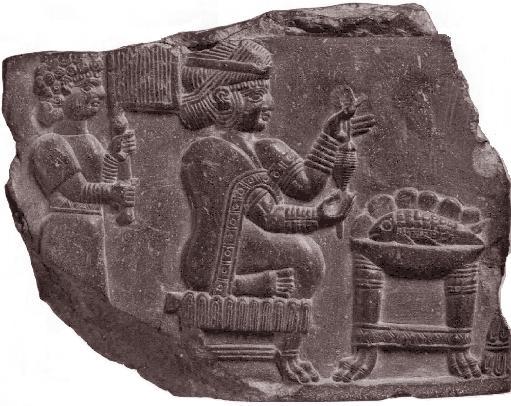

An

elegantly coiffed and well fanned Elamite woman sits on a lion footed

stool winding thread on a spindle. Her servant seems to have settled for

perms. Guess what's for dinner tonight? This five-inch fragment is dated

8th century BC. It was molded and carved from a mix of bitumen, ground

calcite, and quartz. The Elamites used bitumen, a naturally occurring

mineral pitch, or asphalt, for vessels, sculpture, glue, caulking, and

waterproofing. This elegant Elamite Lady has quite appropriately taken

residence in Paris, at Musee du Louvre.

|

|

Ferdowsi Tousi, at Ferdowsi

Square, Tehran. |

|

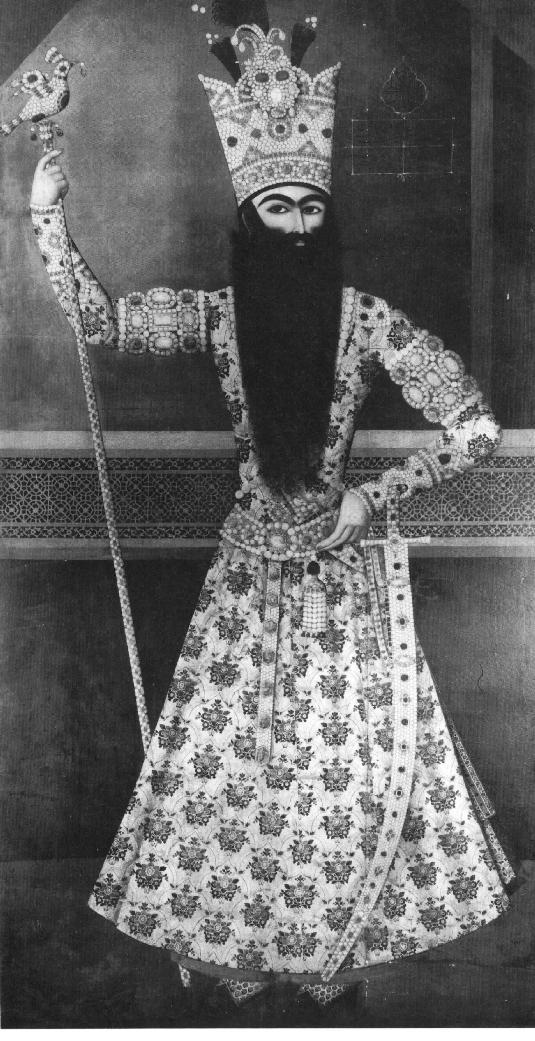

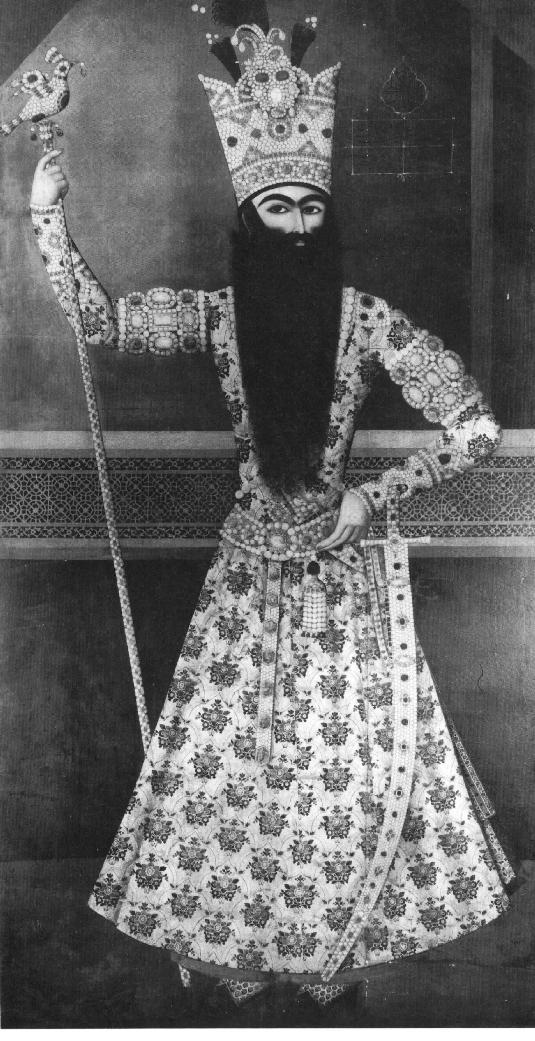

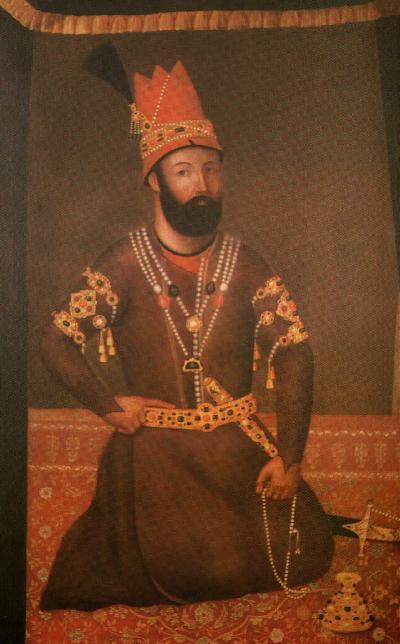

Fath Ali Shah Ghajar, painting

by Mir Ali, Negarestan Museum, Tehran

|

|

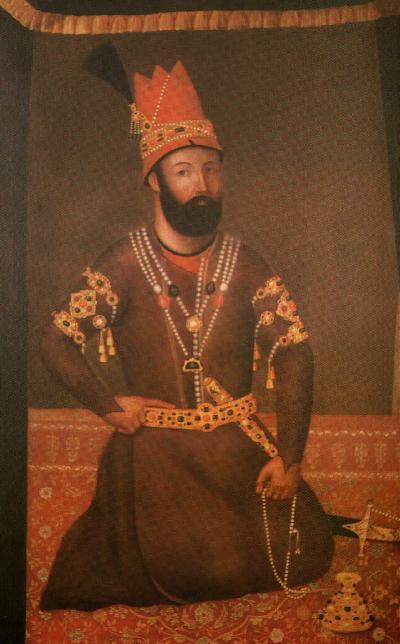

Nader Shah

Afshar

1736-1747

Victoria & Albert Museum, London

|

|

Nezami Ganjavi

|

|

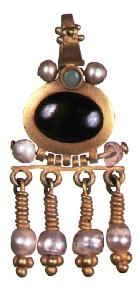

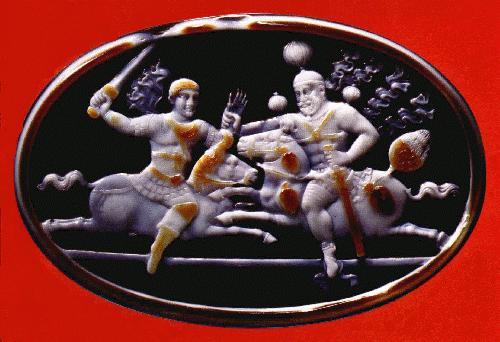

Greek Pendant showing

Alexander and Roxane

Alexander married Roxane who was

Darius III's daughter, he also urged his Generals to follow suit and wed

Persian wives. They had a son together. Mother and son were murdered soon

after Alexander died.

|

|

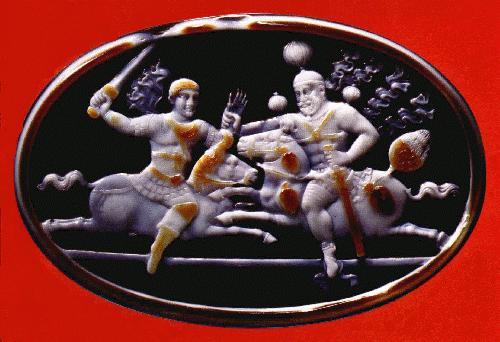

With

Phillp the Arab on his knees and Valerian the Roman Emperor captured,

Shahpour I recorded his Triumph over the Romans, (AD 259 at Edessa

defeating a force of 70,000) here at Nagsh-i Rostam.

|

|

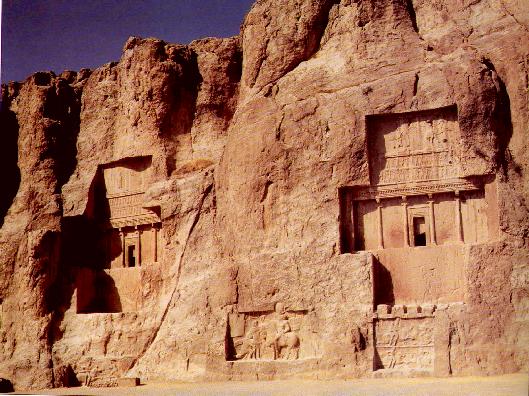

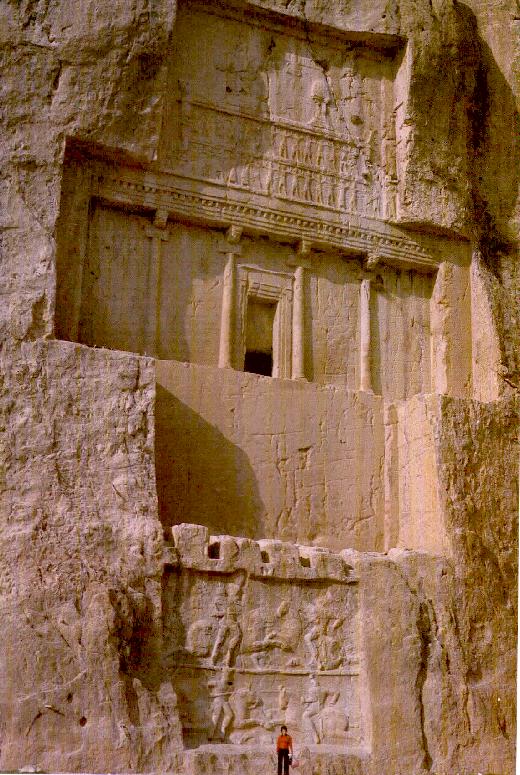

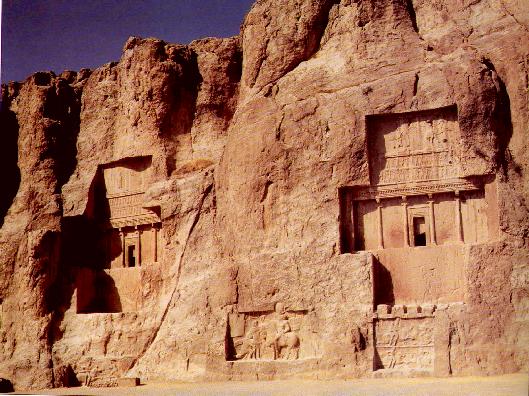

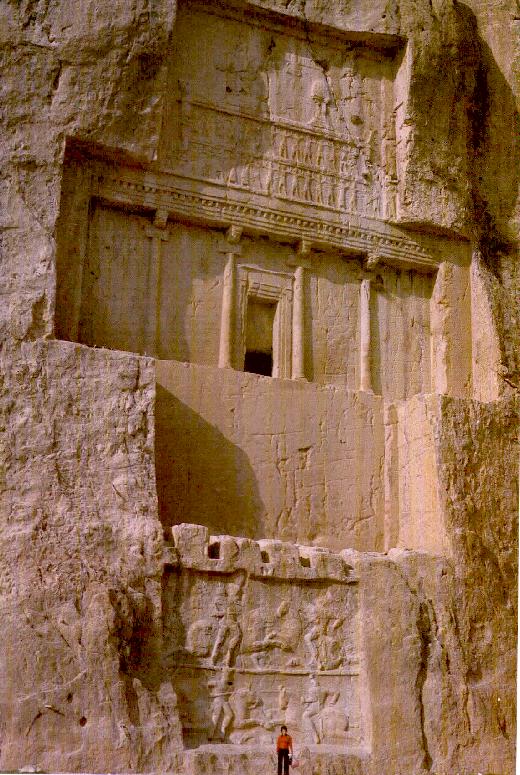

Four

Achaemenid kings- Xerxes I, Darius I, and II, and Artaxerxes I- had

their tombs cut into the cliff face at Nagsh-i Rustam. Only Darius I's

on the right is identified by inscriptions. Each + shaped facade is

over 75 feet high and 60 feet wide. The reliefs below the tombs were

added in the 3rd century AD by Sassanian kings. The one in the middle

shows Shahpour's Triumph over the Romans (Valerian). The cross + has

deep spiritual meaning signifying ascendance to the supreme.

|

|

Darius the Great's crypt

contains three chambers, each with three burial cists. The reliefs

underneath were added 600 years later by the Sassanians. These depict

Ardeshir and his son Shahpour in combat and defeating the Parthians.

|

|

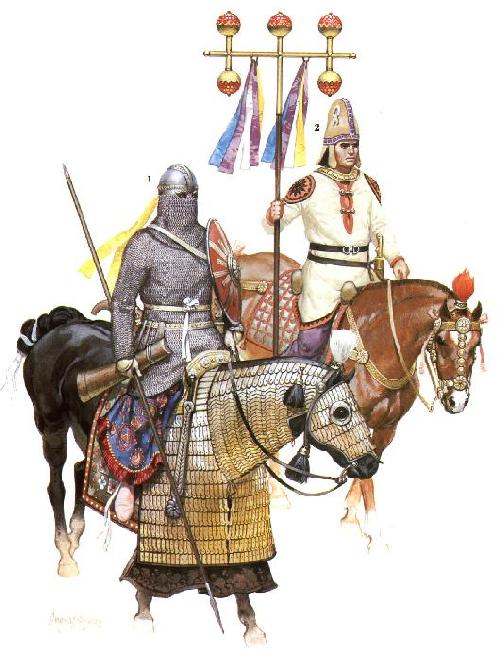

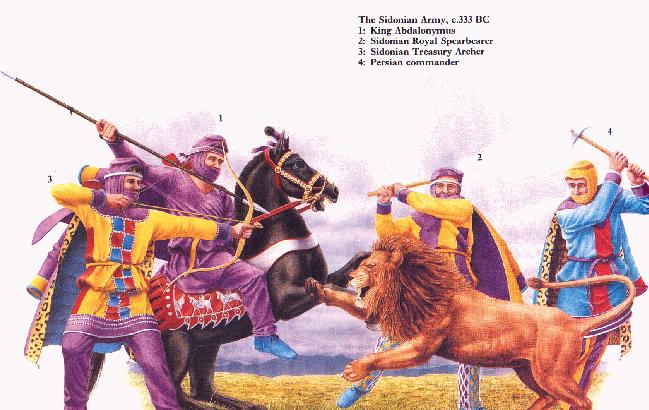

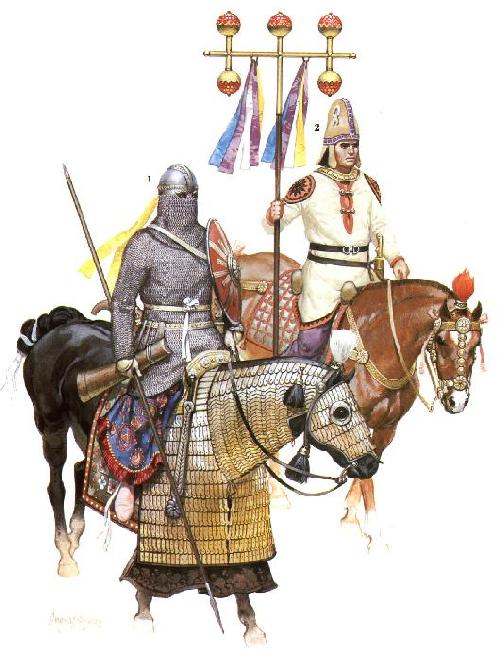

1: Early Sassanian cataphract,

3rd century AD

2: Parthian cataphract

3: Sassanian standard bearer

|

|

1: Sassanian clibanarius, 7th C.

AD

2: Sassanian standard bearer

Under Shahpour I's brilliant

leadership the Sassanian army gave much of its attention to winning

back the cities of Syria that had fallen to Rome during the Parthian

Era.

Sassanian forces were described

by Ammianus Marcellinus, a 4th century historian with the Roman Army

as ".. clad in iron, with all parts of their body covered,

including their heads."

Shahpour's campaigns culminated

in the capture of Valerian the Roman Emperor in AD 259 at Edessa

defeating a force of 70,000.

Upon his return from the Syrian

campaign, Shahpour set building himself a city known as Bishapur (the

beautiful city of shahpour). Roman Ghirshman the French archaeologist

described it as the Sassanian Versailles believed to have had

about 80000 inhabitants.

|

|

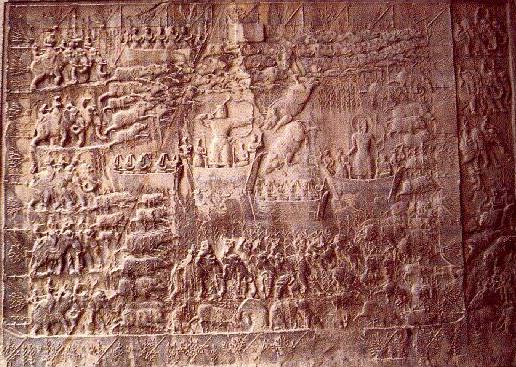

Royal hunt rock relief, great

groto, Tag-i Bustan. Shows the king in the centre from a boat; he is

accompanied by a 2nd boat of harp playing musicians. The king is Khosro

II.

|

|

Investiture of Ardeshir I,

between deities Ahura Mazda and Anahita |

|

Great Groto at Tag-i Bustan

Top: Investiture of Ardeshir I

Bottom: Great Knight

|

|

Susa's

Chateau, so named because it was reconstructed in 1890 by the French

Archaeologist Jacques de Morgan from recycled Elamite and Achaeminian

bricks. This is close to the Susa Acropolis which he dug. Up to 1927 the

French had a monopoly agreement for excavations in Iran hence the Louvre

has an extensive collection of Elamite Artifacts.

Susa always

the pride and joy of the Elamites and the Achaemenids, was settled

around 4500 BC and lasted over 5000 years before finally demolished by

the Mongols in the 13th century AD.

|

|

Bagh Eram, ( Eram Garden )

Shiraz.

This delighful house and garden

used to belong to the Ghavam family. Ghavam Saltaneh was the Prime

Minister of Iran during the Reign of Mohamad Reza Shah.

|

|

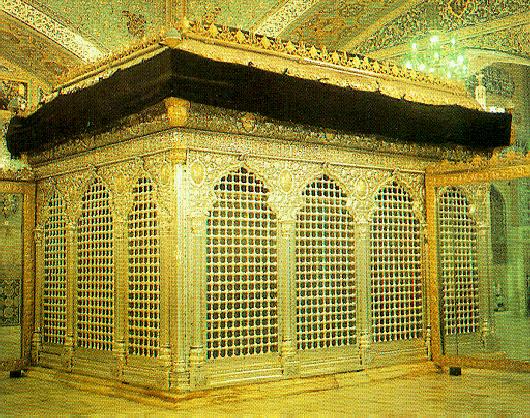

Qom, Mausoleum of Fatima |

|

Taq-i

Kasra (arch of Khosro), Ctesiphon. Drawn 1824 by Captain Hart.

Khosrow I

was renewned for his military and diplomatic skills and is reputed as

the "Just" Anoushirvan Adel. During his time the game

of chess had been brought to his court from India, and his chief

minister Buzarjomehr is reputed to have invented Backgammon.

The splendor

of Khosrow's palace at Cetesiphon ( Tag-i Kasra ) is legendry. The

Throne room was more than 110 ft high. The massive barrel vault covered

an area 80ft wide by 160 ft long. His throne was supported by winged

horses and cushioned in gold brocade, was set at the back behind

curtains, open only during audience. His huge silver and gold crown was

adorned with pearls, rubies, and emerald. The crown so heavy that it had

to be suspended above his head by a gold chain so fine that visitors

were unable to tell that he was not wearing it. When people kneeled in

front of him, it was on silk rugs with a garden design which was placed

on marble floors.

|

|

Shapour II

Details of gilded silver plate

|

|

Gilded silver plate, Freer Art

Gallery |

|

Gilded silver plate, Shapour II

|

|

Silver Dish 7th Century from

Khorasan

Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg

|

The Lion

Overpowering a deer is a recurring theme in Persian Art.Believed

to have the same connotation as Herkle defeating the Water-Ox,

or Mithra killing the bull.

|

|

Central radiant Sun.

Much like the motifs at persepolis |

|

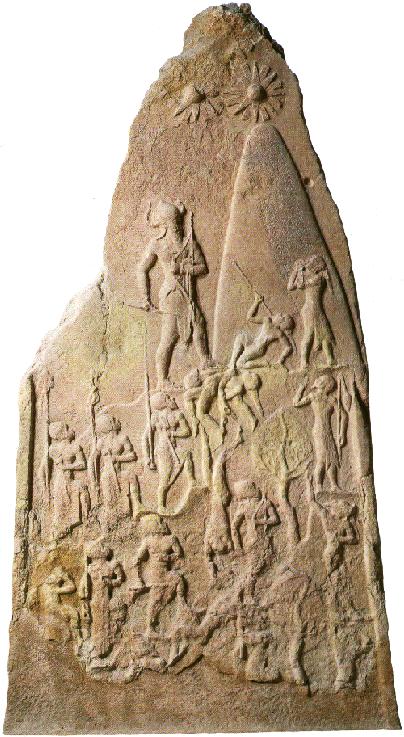

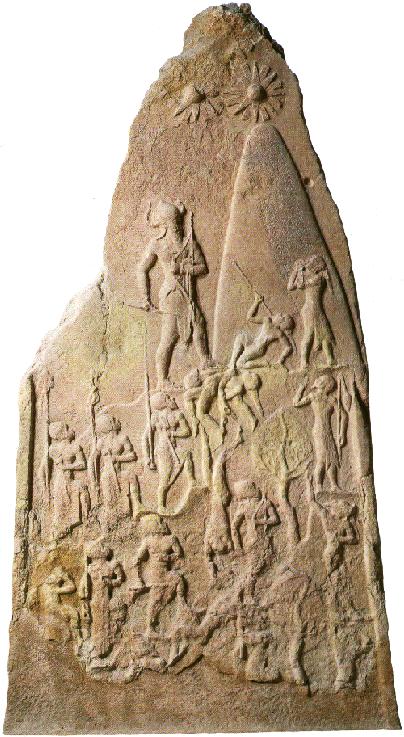

Victory stele, showing the symbol

of the Sun at the summit, 2250 BC.

Excavated from Susa (Shoush). Musee du Louvre, Paris.

|

|

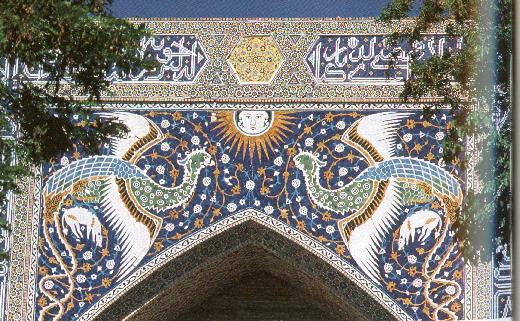

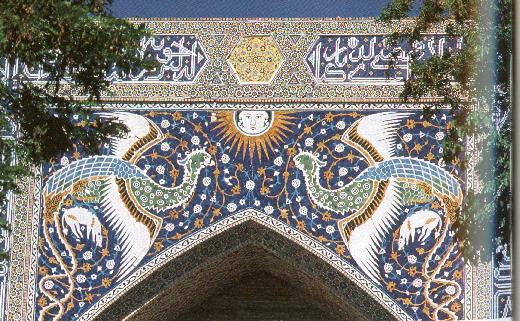

The Sun shines bright at the

center of this gateway.

17th Century Bukhara. |

|

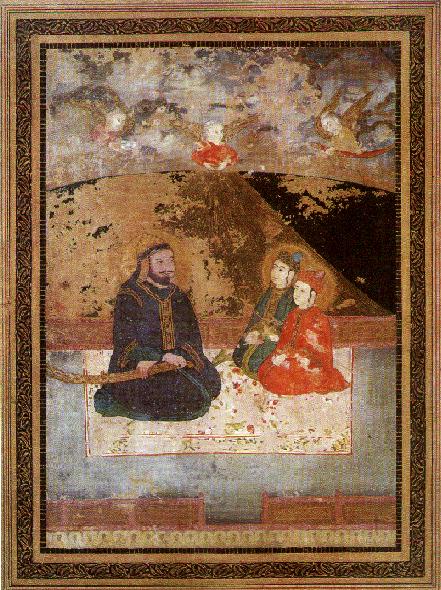

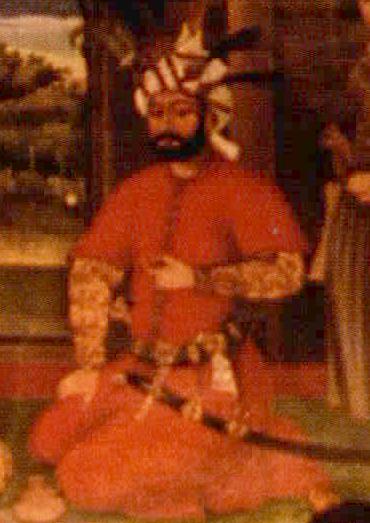

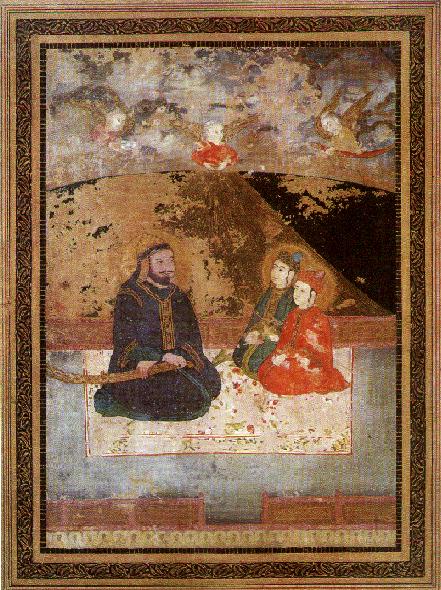

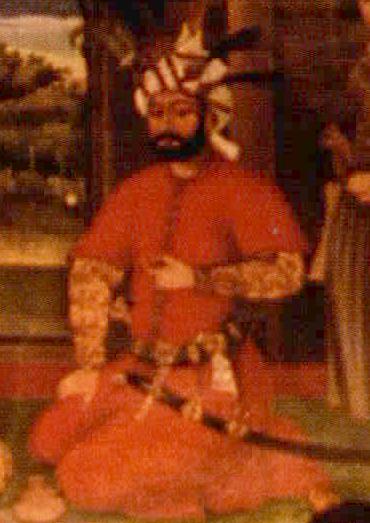

Shah

Tahmasb Safavi

Detail of a

large historical painting on the west wall of the audience hall of the

Chehel Sutoon. |

|

Shah

Tahmasb safavi receives Homayoun Padeshah of India.

Large

historical Painting, west wall of the audience hall of Chehel sotoon.

Maydan Shah, Isfahan. Painted about 1660. Cleaned and restored 1965-74.

|

|

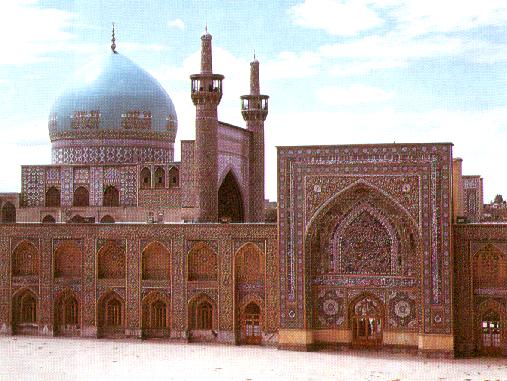

Goharshad Mosque, Mashad

Emam Reza Mausoleum,

Mashad

Emam Reza Shrine Mashad

|

|

Shazdeh Ebrahim Mausoleum, Kashan

|

|

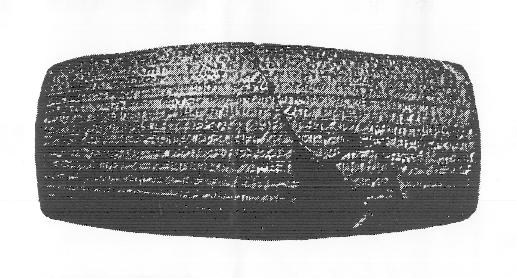

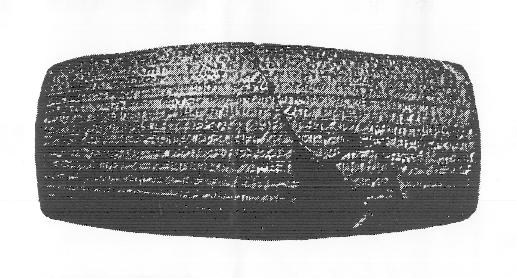

Cyrus's Charter of the

Rights of Nations

Inscribed on a clay cylinder in cuneiform

discovered in 1879 now in The British Museum, London. |

|

Persepolis

General view Persepolis, Fars,

Iran

|

Its ancient

name was Parsa to ancient Persians, it modern

name is Takht-e Jamshid, (Persian: Throne

of Jamshid), to Iranians it was the capital of the Achaemenian

kings of Iran (Persia). Persepolis is located about 50 kms

northeast of Shiraz in the province of Fars

in southwestern Iran. It was set on fire by Alexander upon his

defeat of Darius III.

|

Faravahar or Farohar,

Zoroastrian Symbol

Color reconstruction from Persepolis

|

The Faravahar,

or Farohar, is to remind one of the purpose of

life on this earth, which is to live in such a way that the soul

progresses spiritually and attains union with Ahura-Mazda

(the Wise Lord); this state is called Frasho-kereti in

Avesta.

In the

center of the figure is a circle which represents the soul of

the individual. For the soul to evolve and progress, it has two

wings. In each wing there are five layers of feathers. These

remind one of the five jzhirums with which the soul is linked.

To achieve the ultimate goal of reaching Ahura-Mazda, the soul

has to pass through all the jzhirums. The five layers can also

represent the five Divine Songs (Gathas) of Zarathustra,

the five divisions of the day (Gehs), and the five senses

of the human body.

In nature,

there exist two opposing forces: Spenta-Mainyu the

good mind or assar-i roshni and Angre-Mainyu

the wicked mind or assar-i tariki. A continuous conflict

goes on in nature between these two. A person's soul is caught

between the two and is pulled by each from side to side. The two

long curved legs on either side of the circle represent these

two forces.

To help the

soul balance itself between these two forces, the soul is given

a rudder in the form of a tail. This tail has three layers of

feathers, which reminds one of the path of Asha Humata

(Good Thoughts), Hukhta (Good Words), and Hvarasta

(Good Deeds), or Manashni, Gavashni,

and Kunashni by which the soul is able to make

its own spiritual progress.

The head of

the figure reminds us that Ahura-Mazda has given every soul a

free will to choose either to obey divine universal natural laws

or to disobey them.

The figure

also has a pair of hands which hold a circular ring. The ring

symbolizes the cycles of rebirths on this earth and other planes

which the soul has to undergo to make progress on the path of

Asha. If these divine laws are obeyed through Manashni, Gavashni,

and Kunashni, our soul will be able to attain union with

Ahura-Mazda. This far-off event, towards which the whole of

creation moves, is called Frasho-kereti.

|

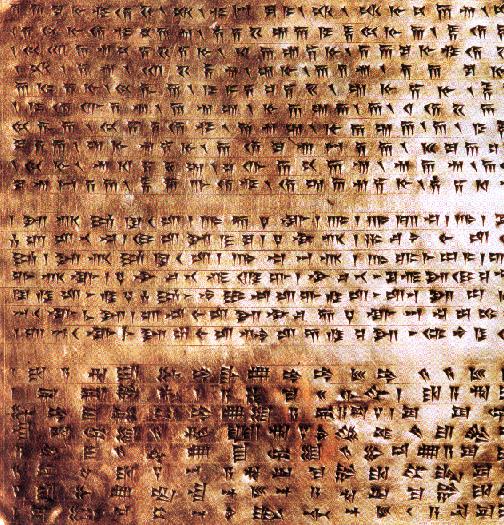

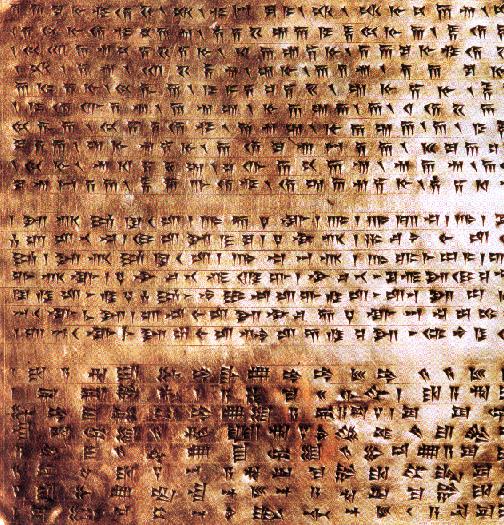

Cuneiform script, gold tablet

discovered by German Architect Freidrich Krefter, Apadana Palace

Pesepolis, 1933. Inscribed in Old Persian, Elamite, and Babylonian, it

identifies Darius I as the builder of Apadana.

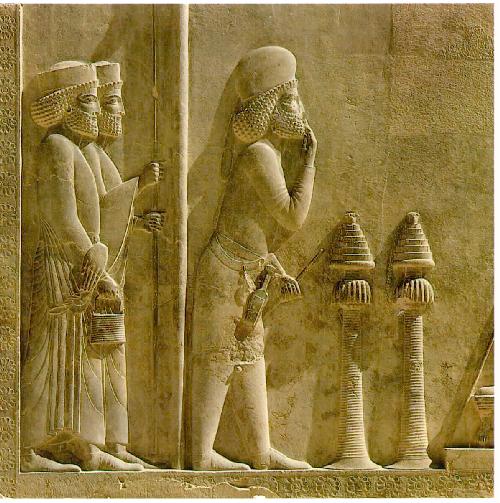

Apadana Palace, Persepolis

Built

by Darius I of the Achaemenids this palace is the most awe inspiring

monument of the Persians. To be there and get close to the life size

figures on the Bas-relief takes one back thousands of years, or maybe

brings them to the present. The atmosphere instantly portrays the

feeling of magnificence mixed with outrage emotion towards those

ignorant souls who through history have made its distruction their

life's ambition.

A Mede at the foot of

Darius I while two guards stand in attention,

Apadana Palace, Persepolis

Darius

the Great

(521-486 BC)

Enthroned

in Peresepolis, the magnificent city that he built, Darius I firmly

grasps the royal scepter in his right hand. In the left, he is holding a

lotus blossom with two buds, the symbol of royalty.

This

Bas-relief is at the Apadana Palace, Persepolis, showing Darius

receiving Iranian delegates at audiance during the New Year (Nowrouz,

March 21st) festivities.

The reliefs

portray different peoples who were part of the Achaemenid Empire, each

group identified by its native costume. The tributaries, carry

indegenous valuable gifts to be offered to the king during the New Year

ceremony.

King under the parasol, south door

of central building Persepolis

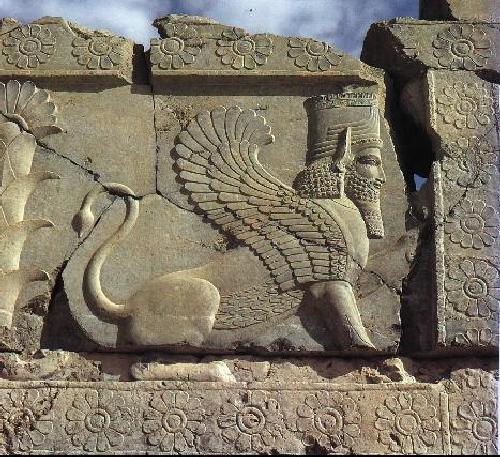

Fighting a griffin, Darius

palace, Persepolis.

Majesty of a lion,

high-flying as a bird, intellect of a human; Bas-relief Persepolis

Bas Relief Persepolis

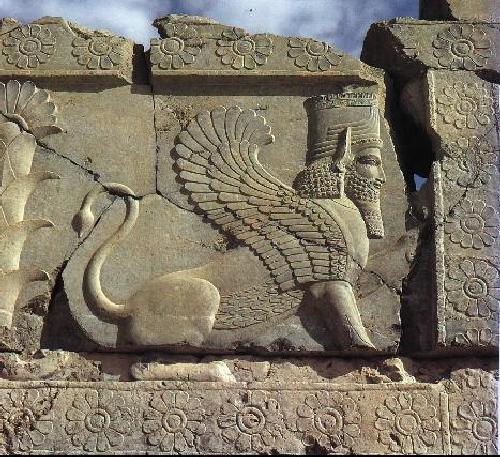

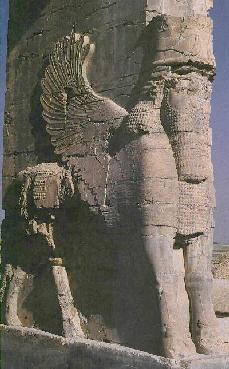

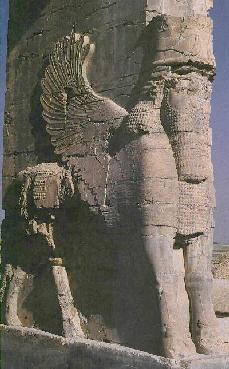

Winged

bull with human head, Xerxes' gate Persepolis

|

|

Pre-Achaemenid:

|

|

Elamite king at worship,

gold and silver statuette 12 Century BC,

3" high

discovered 1904 by archaeologist Roland de Mecquenem at Susa's

(shoush) acropolis.

|

|

14th Century BC Statue of

Queen Napir-Asu of Elam

found in 1903, temple of Ninbursag,

Susa (Shoush), it weighs 3760 pounds |

|

Silver bull

figurine c.3000BC

Metropolitan Museum of Art,

New York

|

|

An

elegantly coiffed and well fanned Elamite woman sits on a lion footed

stool winding thread on a spindle. Her servant seems to have settled for

perms. Guess what's for dinner tonight? This five-inch fragment is dated

8th century BC. It was molded and carved from a mix of bitumen, ground

calcite, and quartz. The Elamites used bitumen, a naturally occurring

mineral pitch, or asphalt, for vessels, sculpture, glue, caulking, and

waterproofing. This elegant Elamite Lady has quite appropriately taken

residence in Paris, at Musee du Louvre.

|

|

What Robert Dyson the

archaelogist from the University of Pennsilvania called "the

discovery of a lifetime". Gold cup from Hasanlo, northwest Iran.

Click on the image above to see Dyson, his discovery and his jeep called

Darius in 1957.

|

|

Golden Vase, From Tape Marlik,

1000 BC |

|

Achaemenid:

|

|

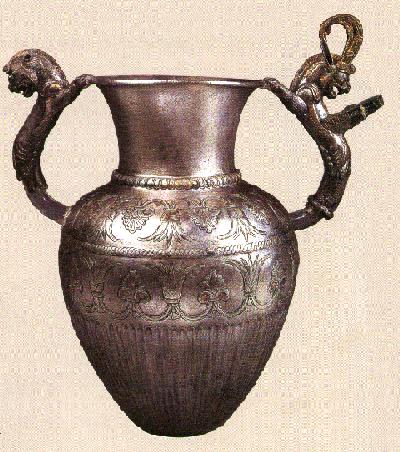

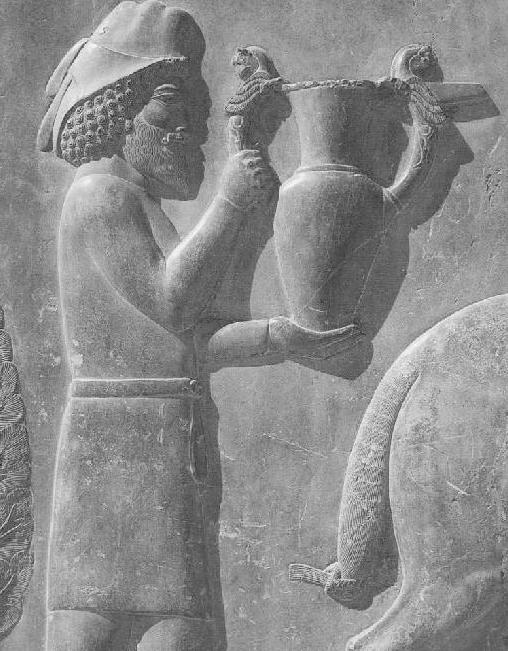

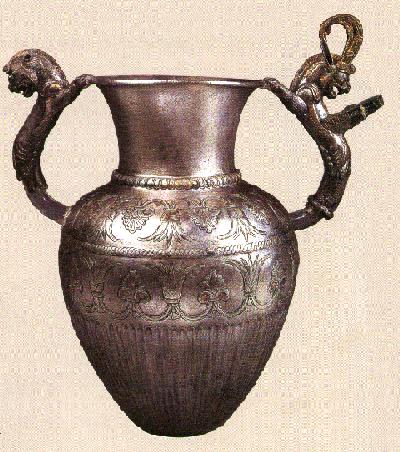

Amphora silver, used for wine at

banquets. This is like the one carried by the Armenian delegate at

Apadana wall relief

|

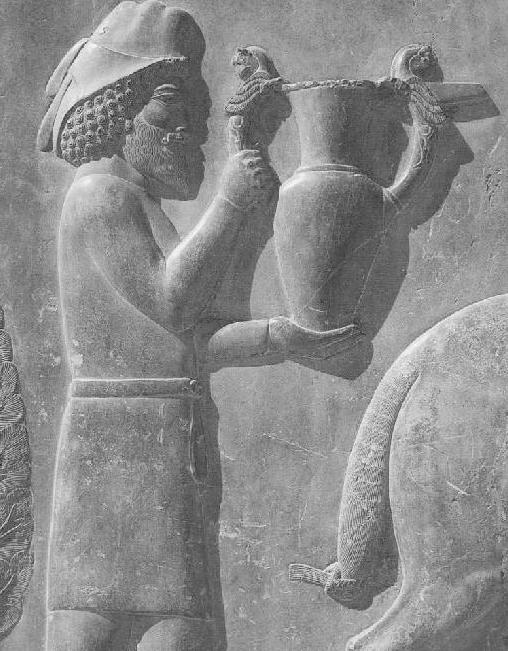

|

An Armenian carrying an amphora,

these were used for wine at banquets. Rearing lions make the handles one

of which is also the spout

|

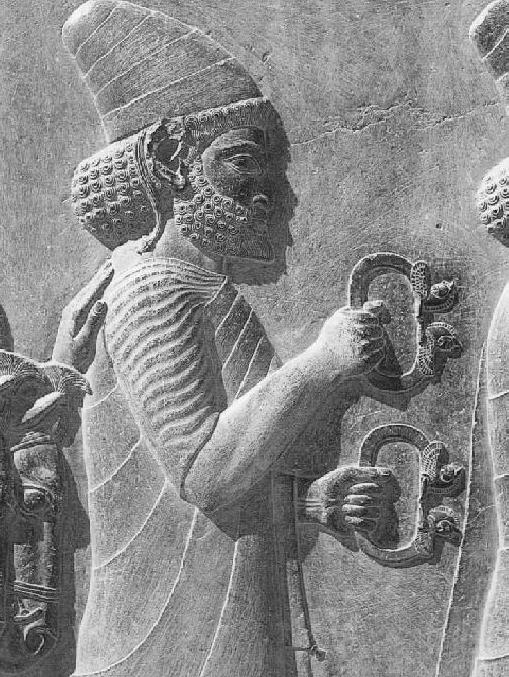

|

An exquisit example from the

"Oxus Treasure", similar to the armlet carried by the Lydian

on the rock relief at Apadana, Persepolis.

|

|

A Lydian bringing gold armlets

to present to the king. Apadana Audience Hall.

|

|

Gold Belt Buckle Achaemenid

|

|

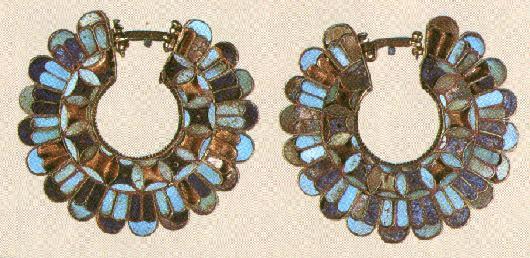

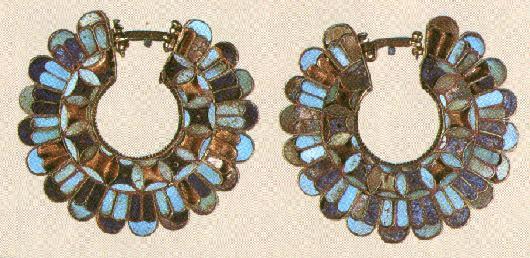

Pair of

earings inlaid with turquoise and lapis lazuli. Achaemenid period worn

both by men and women

|

|

Glass Jar, Achaemenid |

|

Gold Rhyton, Achaemenid

period

|

|

A

gold bowl similar to one's depicted in Persepolis. The lion motif

handles are common in Persian Art. This bowl was presented to Peter

the Great, Czar of Russia by the governor of Siberia, probably from a

Scythian tomb.

|

|

Achamenid Gold Jewelery, part of

the Oxus Treasure

British Museum, London

|

|

Gilded silver Rhyton, Achaemenid

|

|

Parthian:

|

|

............. .............

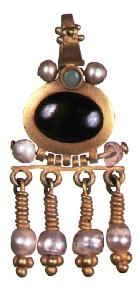

On the left, 3rd century AD, gold

& spinel (ruby like gem) from Hatra

On the right, 2nd century AD, gold and pearl, inset with garnet, from

Seleucia.

|

|

Parthian fashion of 2nd century

AD, wearing a flowing gown, headress, and jewels.

|

|

Sassanian:

|

|

Sassanian gold dinar of

Shapour II, circa 310 AD.

|

|

Ewer gilted silver, late

Sassanian with dancer motif, repeated on all sides.

|

|

Gilded silver plate, Freer Art

Gallery

|

|

Shahpour I grasps the arm of

Valerian

the Roman Emperor signaling his capture AD 260

|

|

Silver horse

with gold foil enhancements, 3rd century AD, Sassanian. Served as a

ceremonial rhyton, with the forelock as the funnel and an opening in the

chest as the spout.

|

|

Middle section of a Sassanian

Tapestry

|

|

Post-Islamic:

Metalwork:

|

|

Brass

ewer, inlaid with copper and silver, late 12th century Herat, Brithish

Museum , London. Click on the image above to see details of

a larger picture.

|

|

10th century gold jug,

inscribed Bakhtiar-ibn Moazedowleh

Detail of 10th centuray gold jug

|

|

Gold Vase, old immitation,

possibly by Parvaresh in Esfahan |

|

Various

objects- silver with gilding from North of Iran, 12th century, L.A.

Mayer Memorial Institute, Jerusalem

|

|

Rosewater sprinkler, gilded silver

and niello inlaid. 12th century AD. Freer Gallery of Art, Washington

|

|

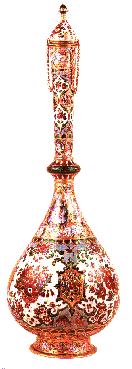

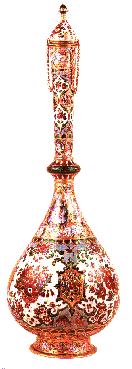

Rosewater

sprinkler, enamelled gold, late 18th century

|

|

Amir

al Momenin, and his two sons, Emam Hassan and Emam Hussein. Late 16th

century. Unusual as it portrays them in helmets.

|

|

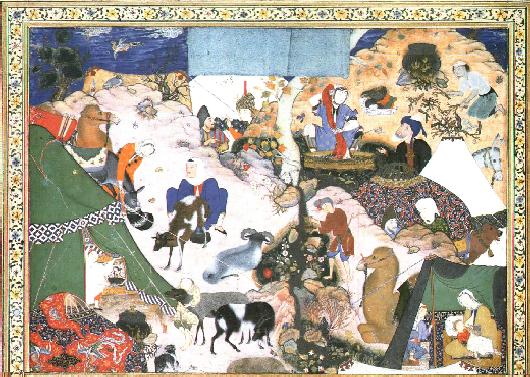

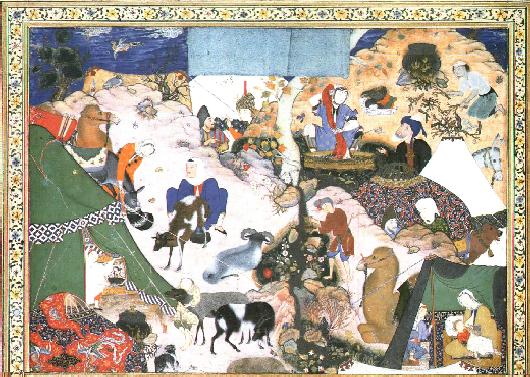

From the book of Khamseh Nezami

done for Shah Tahmasb, done by Mir, Seyed Ali, Tabriz, 1540. Fogg Art

Museum, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA

Detail of Camp Life

|

|

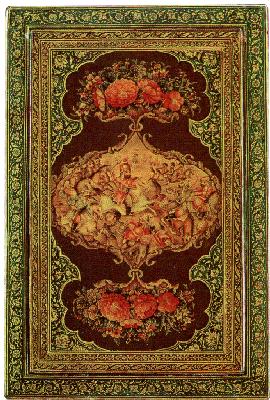

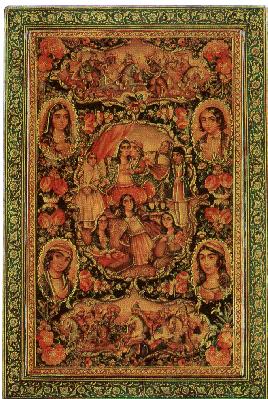

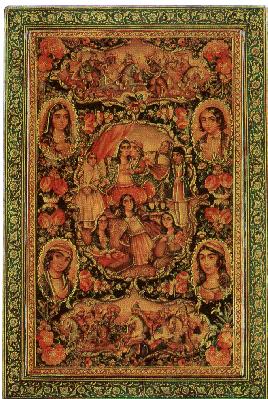

Two mirror lids by Mirsa Baba,

late 18th century from Shiraz. The one on the left depicts fighting

scene in the middle. The one on the right possibly a wedding gift also

shows fighting scenes on top and bottom.

|

|

|

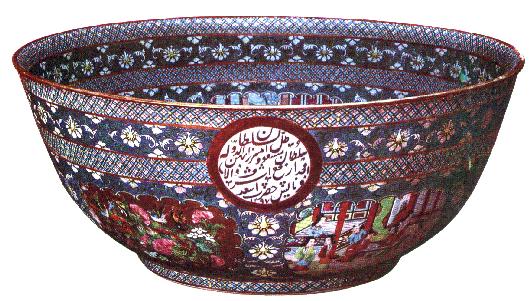

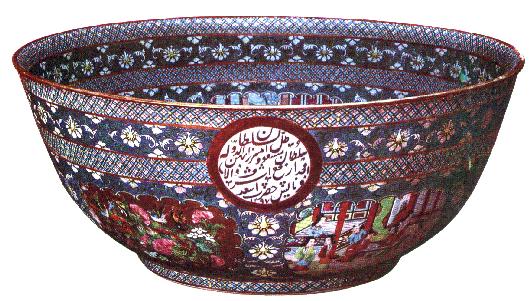

Porcelain services from China and

Japan have been imported with great difficulty since the 18th century.

An extensive collection of such Chinese porcelain is housed at the

Golestan Palace in Tehran. The bowl above is 60cm in diametre, part of a

dinner service from Canton possibly for 200-300 guests. The Medalion

bears the name of the orderer. Zel Sultan the son of Nasser Din Shah

dated 1297 hejri/1901 AD.

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

|

Iran In Louvre Museum |

|

|

|

Boisseau de Suse I

Suse: nécropole archaïque

Vers 4000 avant J.-C.

Terre cuite

H 0,285 m;

L 0,160 m

Sb 3174

Les vases peints déposés dans les tombes des premiers Susiens

illustrent, à la veille de son extinction, l'apogée de la

tradition néolithique des peuples montagnards descendus dans la

plaine. Les formes sont simples et harmonieuses; le décor hardiment

stylisé. On reconnaît en haut une frise d'échassiers étirés en

hauteur; au-dessous, des chiens courants, étirés horizontalement,

et en bas, un grand bouquetin aux formes géométriques et aux

cornes démesurées, dessinant un ovale presque parfait. Cette

stylisation rappelle de façon trompeuse celle de signes

pictographiques. En réalité, elle est purement décorative, comme

l'atteste sa diversité d'un vase à l'autre. Avec de tels vases

pouvaient être mis à la disposition des morts des objets, telle

une hache en cuivre, importés d'Iran central.

|

|

|

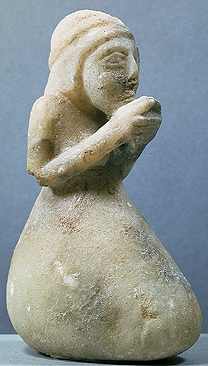

|

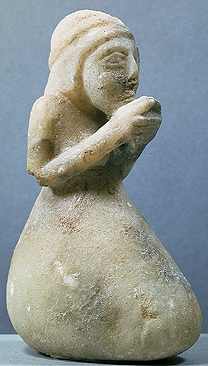

Orante

Suse, époque récente d'Uruk

Vers 3300 avant J.-C.

Statuette, albâtre

H 11,5 cm; L 4,5 cm

Sb 69

L'adoption de la civilisation urbaine de type sumérien amena les

Susiens à créer des arts appelés à devenir classiques. Rompant

avec la stylisation purement décorative des périodes préhistoriques,

ils adoptèrent le réalisme pour idéal. C'est ainsi qu'ont été

taillées des statuettes de dévotes, à la fois délicates et

pleines d'humour, agenouillées dans leur robe selon la tradition

propre au monde iranien.

|

|

|

|

Pièces de comptabilité archaïque

Suse, époque récente d'Uruk

Vers 3300 avant J.-C.

Argile légèrement cuite

Ø 6,5 cm

Sb 1927

Obligés de gérer la richesse considérable suscitée par le développement

de type urbain, les Susiens créèrent une comptabilité. Ils

commencèrent par matérialiser les nombres par de petits objets

d'argile analogues aux cailloux utilisés par d'autres civilisations

antiques et qui ont donné son nom à notre calcul. Ils les plaçaient

dans des boules creuses d'argile pour éviter leur dispersion. Le

nombre ainsi symbolisé pouvait être reporté sous forme d'encoches

à la surface de la boule-enveloppe sur laquelle on apposait le

sceau désormais cylindrique du scribe, comme garantie d'authenticité.

Ces encoches sont les premiers signes graphiques proprement dits,

que l'on reporta bientôt sur de petits pains d'argile ou "tablettes"

en attendant de préciser leur signification par des signes

conventionnels. Le processus d'invention de l'écriture était ainsi

engagé, grâce à la comptabilité.

|

|

|

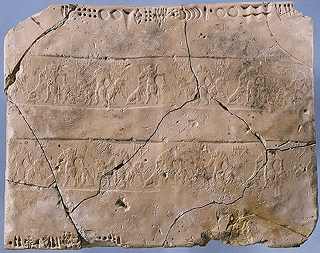

Tablette géante proto-élamite

Suse. Tell de l'Acropole

Epoque de Suse III ou époque proto-élamite (vers 3100-2850 avant J.-C.)

Argile crue

H 21 cm; L 26,7 cm

Sb 2801

L'écriture proto-élamite, toujours pas déchiffrée, figure sur cette

tablette géante de comptabilité dont les empreintes de cylindre évoquent

les triomphes alternés du lion et du taureau représentés en attitude

humaine.

|

|

|

Déesse élamite

Suse

Vers 2100 avant J.-C.

Statue, calcaire

H 1,09 m

Sb 54

Le prince de Suse, Puzur-Inshushinak, réussit à créer un

empire élamite double englobant la plaine susienne de langue sémitique,

et le plateau de langue élamite. Il inscrivit ses monuments en deux

langues: l'akkadien sémite et l'élamite rédigé en une écriture

linéaire nouvelle, encore mal déchiffrée. La statue à

inscription bilingue représentant la grande déesse -probablement

Narunte ou Narundi- lui attribue l'aspect de l'Ishtar mésopotamienne,

trônant sur des lions. Sa tiare à cornes est semblable à celle

des divinités du temps de Gudéa, prince de Lagash, sensiblement

contemporain.

|

|

|

|

Coupe tripode aux bouquetins

Suse

Début du IIe millénaire avant J.-C.

Mastic de bitume

H 18,5 cm; Ø 28 cm

Sb 2737

La prospérité dont bénéficia Suse au début du IIe millénaire

est attestée par la richesse du mobilier des tombes. Outre des

parures d'or et d'argent, on plaçait à la disposition des morts de

la nourriture dans de la vaisselle commune et dans des vases de luxe

taillés dans le mastic de bitume pour imiter une pierre exotique.

L'exemple le plus remarquable est une coupe tripode reposant sur des

pieds en forme d'avant-train de bouquetins.

|

|

|

|

Statuette composite

Bactriane

Début du IIe millénaire avant J.-C.

Chlorite et calcaire

H 17,3 cm

AO 22918

A la fin du IIIe millénaire et au début du IIe, la civilisation

trans-élamite essaima au-delà de l'Iran, jusqu'aux confins de

l'Asie Centrale, en Bactriane (Afghanistan du Nord). Le mobilier des

tombes creusées à proximité de forteresses très élaborées

comprenait des objets d'usage courant et de luxe, témoins d'une

civilisation apparentée à celle de l'Elam. A côté de haches

d'apparat servant d'insignes de dignités, comme en Elam, on déposait

dans les tombes des statuettes composites de femmes dont la robe en

"crinoline" est semblable à celles des reines d'Elam;

cette robe a été traitée avec l'archaïsme du "kaunakès"

de l'époque des dynasties archaïques.

|

|

|

|

Dieu élamite

Suse

Vers 2000 avant J.-C.

Cuivre et or

H 17,5 cm; L 5,5 cm

Sb 2823

La dépendance culturelle de Suse à l'égard de la Babylonie

resta grande au début du IIe millénaire, alors que la ville

appartenait au royaume élamite. Les dieux étaient donc représentés

comme ceux de Mésopotamie, vêtus de la robe à volants du "kaunakès"

et coiffés de la tiare à plusieurs paires de cornes symboliques de

la puissance divine. Celui-ci se distingue par son sourire, absent

des effigies mésopotamiennes. Il était à l'origine entièrement

revêtu d'un placage d'or qui ne subsiste que sur la main.

|

|

|

|

Portrait funéraire d'un Elamite

Suse

XV-XIVe siècles avant J.-C.

Terre crue peinte

H 24 cm; L 15 cm

Sb 2836

Au milieu du IIe millénaire, les Susiens enterraient leurs morts

dans des caveaux familiaux, sous le sol des maisons. Ils plaçaient

souvent à côté de la tête, sans doute voilée, un portrait exécuté

sitôt la mort venue. C'est le seul exemple en Orient d'un art funéraire

proprement dit, s'attachant à fixer les traits personnels. Celui-ci

représente l'Elamite type, au visage sévère, caractéristique

d'une rude population aux fortes affinités montagnardes.

|

|

|

|

Hachette royale

Tchoga Zanbil, ancienne Al-Untash

Vers 1340-1300 avant J.-C.

Argent et électrum

H 5,9 cm; L 12,5 cm

Sb 3973

Le roi Untash Napirisha d'Elam construisit près de Suse une

capitale religieuse dominée par une tour à étages, consacrée aux

deux dieux-patrons des deux moitiés de l'empire, le haut-pays et la

plaine susienne. A son pied, la déesse-épouse du dieu montagnard,

appelée Kiririsha, avait un temple richement pourvu. On y a trouvé

en particulier cette hachette portant l'inscription: "Moi

Untash Napirisha" inscrite sur la lame crachée par la gueule

d'un lion. Une figurine de marcassin orne le talon de l'arme, qui

renoue avec une tradition spécifiquement montagnarde, créée au

Luristan au IIIe millénaire.

|

|

|

Orants élamites

Suse

XIIe siècle avant J.-C.

Statuettes. Or et argent

H 7,5 cm; H 7,6 cm

Sb 2758-2759

Ces statuettes représentent des orants en prière apportant un

chevreau en offrande à la divinité. Elles étaient destinées à perpétuer

un acte de culte dans un temple. Elles avaient été jointes aux offrandes

funéraires, dans une tombe royale creusée près du temple d'Inshushinak,

patron de Suse. Elle sont très représentatives de la maîtrise des métallurgistes

susiens.

|

|

|

Vase aux monstres ailés

Région de Marlik (Iran du Nord)

XIVe-XIIIe siècles avant J.-C.

Electrum

H 110 cm; Ø 112 cm

AO 20281

Les premiers immigrants iraniens semblent s'être établis dans

le courant du IIe millénaire au nord du plateau auquel ils devaient

donner leur nom. Vraisemblablement nomades, ils se faisaient

enterrer dans des cimetières tels que celui qui a été exploré à

Marlik, non loin du village d'Amlash. Dépourvus de traditions

artistiques, ils s'inspirèrent, pour décorer leur orfèvrerie, de

l'art des vieilles civilisations d'Asie occidentale. Ce gobelet en

alliage naturel d'or et d'argent (électrum) porte ainsi un décor

emprunté au répertoire en honneur dans l'empire mitannien situé

dans le Nord mésopotamien: monstres ailés aux serres entrelacées,

maîtrisant des animaux.

|

|

|

|

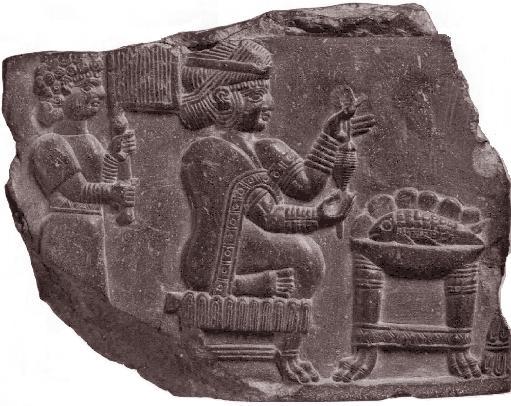

Fragment du bas-relief dit "la

fileuse"

Suse

Période néo-élamite, VIIIe VIIe siècle avant J.-C.

Mastic de bitume

H 9,3 cm; L 13 cm

Sb 2834

Ce petit relief fragmentaire, d'une grande qualité, représente

une jeune femme, probablement de haut rang. Elle est assise à

l'orientale devant une table chargée d'un poisson, de pains ou de

fruits. Elle tourne le fuseau de la main droite et tend les fils de

la main gauche, tandis qu'une servante agite un grand éventail

rectangulaire.

|

|

|

|

Plaque de mors

Luristan (Iran occidental)

VIIIe-VIIe siècles avant J.-C.

Bronze

H 19 cm

AO 20530

Les montagnards du Luristan avaient créé dès le milieu du IIIe

millénaire la tradition d'une riche métallurgie qui subit une éclipse

quand ils se sédentarisèrent au IIe millénaire. Cette tradition

reprit son essor avec le retour du nomadisme, du XIIe au VIIe siècle.

Les bronziers montagnards affectionnaient les mêmes figures que les

peuples urbanisés des plaines, mais en les stylisant selon l'esprit

propre aux nomades restés en marge de l'histoire. Sur cette

remarquable plaque de mors historiée, ils représentèrent un génie

cornu, à l'aile terminée par une tête de fauve piétinant un

bouquetin.

|

|

|

|

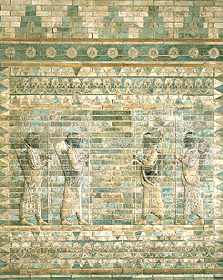

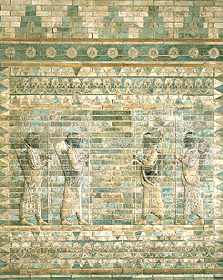

Les archers de Darius

Suse

Vers 510 avant J.-C.

Bas-relief, briques siliceuses à glaçure

H 4,75 m

AOD 488

Darius Ier (522-486 avant J.-C.) fit de Suse la capitale

administrative, où il construisit son palais de tradition

babylonienne, auquel était adjointe une salle du trône, à

colonnes, de tradition iranienne Le décor en briques glaçurées de

ce palais évoque surtout l'armée perse: les archers revêtus de la

robe d'apparat, qui n'était pas leur tenue de combat. Soucieux de

représenter cette robe plissée, selon la tradition attestée précédemment

au Luristan, les émailleurs susiens se sont inspirés du modèle

grec, en le stylisant selon leur génie propre.

|

|

|

|

Chapiteau d'une colonne de la salle d'audiences

(Apadana) du palais de Darius Ier

Suse

Epoque achéménide. Règne de Darius Ier (vers 510 avant J.-C.)

Calcaire

H 3,20 m

AOD 1

L'Apadana du palais de Darius Ier à Suse, située au nord de la

résidence, se présentait comme une vaste salle à colonnes de plan

carré entourée de trois portiques. Les trente-six colonnes à base

carrée de l'espace intérieur atteignaient une hauteur de 21 mètres.

Le chapiteau en calcaire gris était composé d'une paire d'avant-trains

adossés de taureaux qui supportaient les poutres du plafond, de

volutes d'inspiration ionienne. Il manque au-dessous un élément en

corolle palmiforme d'origine égyptienne, et dont quelques fragments

ont été retrouvés. Les trente-six colonnes des portiques avaient

une base campaniforme.

|

|

|

|

Anse de vase achéménide

IVe siècle avant J.-C.

Argent et or

H 27 cm; L 15 cm

AO 2748

Selon toute vraisemblance, cette anse zoomorphe en argent

partiellement plaquée or et son pendant du Musée de Berlin

appartenaient à un de ces vases d'apparat à haut col évasé et

panse ovoïde cannelée que nous montrent les bas-reliefs de Persépolis

et dont quelques exemplaires en bronze ou en métal précieux sont

parvenus jusqu'à nous. Comme leurs ancêtres nomades d'Iran du Nord,

les grands rois perses appréciaient vivement la vaisselle de luxe.

Leurs orfèvres s'inspiraient librement de l'art des peuples de

l'empire. C'est ainsi que ce bouquetin ailé est foncièrement

iranien, mais repose sur un masque de Silène, emprunté aux Grecs

d'Ionie.

|

|

|

|

Buste d'un roi sassanide

Ladjvard, Mazandaran (Iran) ?

Epoque sassanide. Ve -VIIe siècle après J.-C.

Bronze

H 33 cm

MAO 122

Ce buste royal porte les insignes des rois sassanides: la

couronne ailée, la barbe passée dans un anneau, et un pectoral

maintenu par une sorte de harnais. La forme de la couronne qui

variait à chaque règne permet de penser qu'elle appartenait à un

souverain du VIe siècle ou du VIIe siècle après J.-C.

|

|

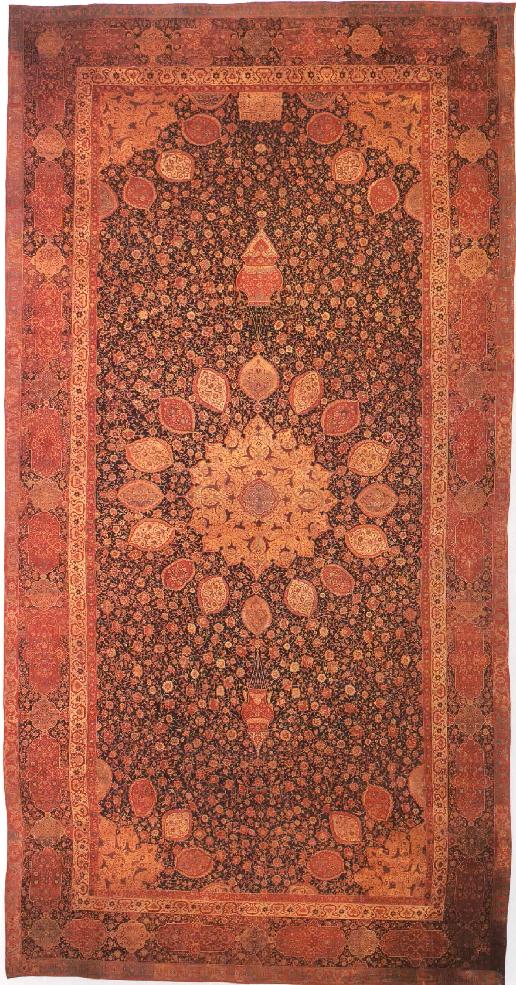

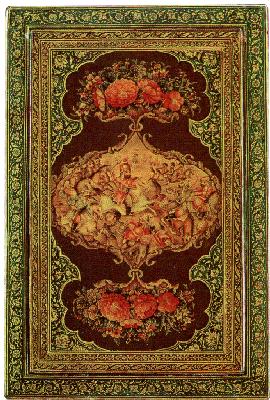

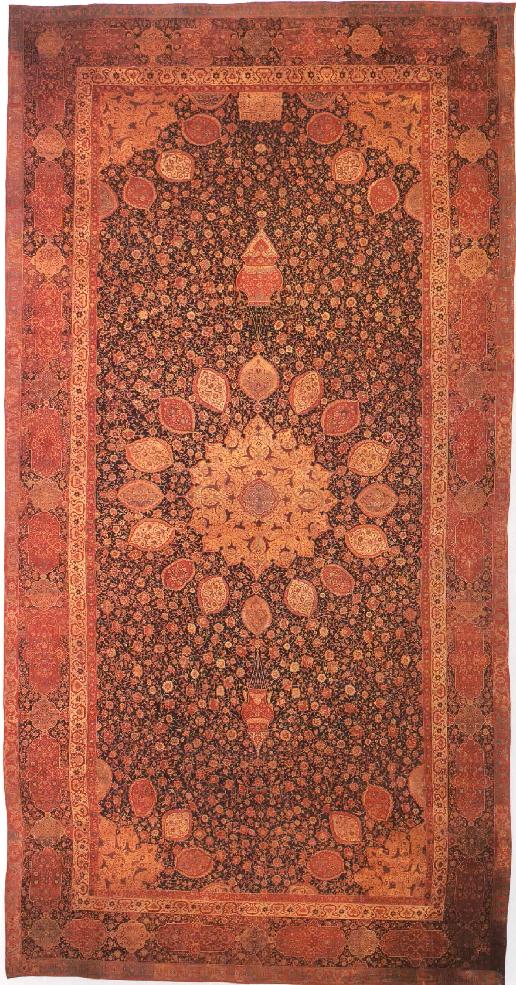

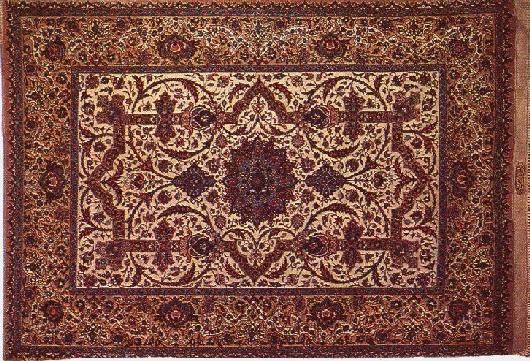

| Carpets

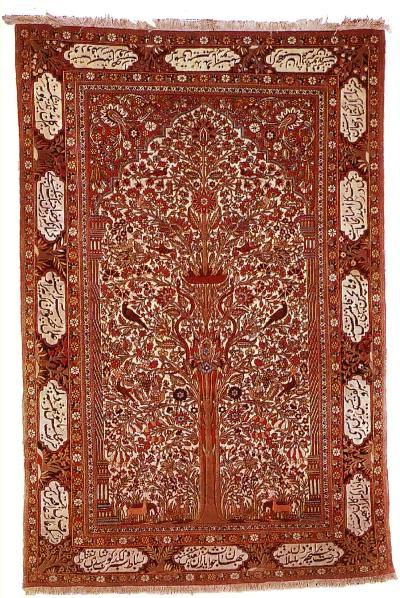

Carpet weaving is truley a Persian

tradition. Xenophon, the ancient Greek historian recorded that in

Achemaenid times the ancient city of Sardis, then subject to the Persians,

prided itself on its carpets. Carpet design in Iran was abstract

expressionism to the highest degree. Each weaving region particular in its

choice of natural dyes, weaving design, and techniques. Persian rugs,

kilims and carpets have the quality of improving with use, but even

dispite this quality no carpet that can be described as Persian can be

dated much before the early 16th century. Only three 16 century Persian

carpets are inscribed with dates. The most notable of these is the famous

Ardabil carpet at London's Victoria & Albert Museum. This Museum also

houses some other magnificent examples of Persian carpets, well worth a

visit for any carpet lover of the Persian kind. |

|

The

Ardebil Carpet, signed Maqsud Kashani and dated 1539-40. Silk warps,

three silk wefts, wool pile, asymmetrical knots. 10.51 x 5.53 M,

Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

|

|

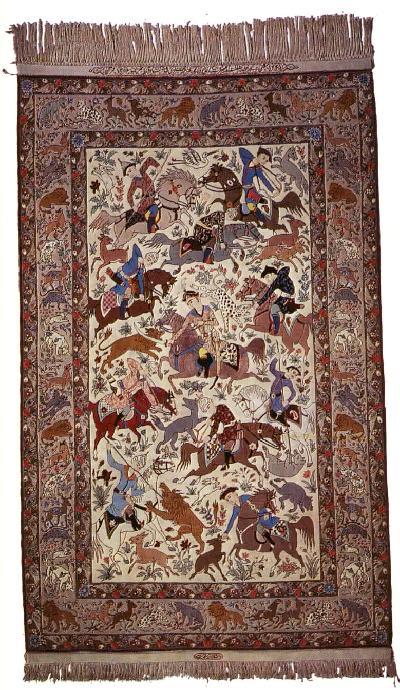

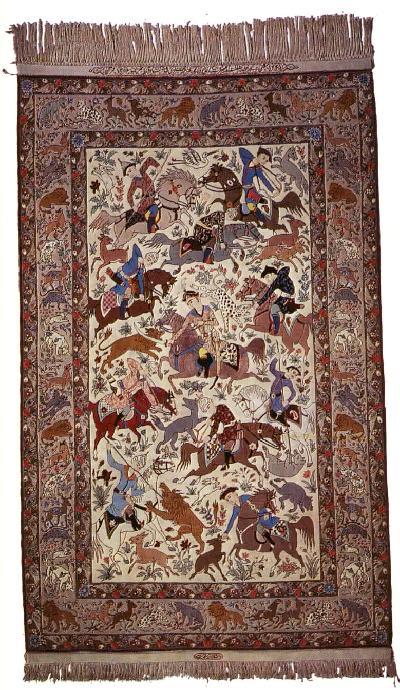

A double

sided silk and wool Esfahan woven to the order of Golamali

Seif-Nasseri by Hekmatnejad. Such double sided carpets were often used

as curtains. This one shows a hunting scene and animal motifs. It took

6 weavers 3.5 years to complete.

|

|

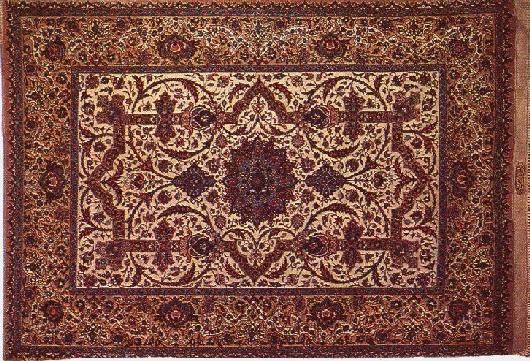

Isfahan Hekmatnejad, motifs are

taken from the inside of the mosques in Isfahan.

|

|

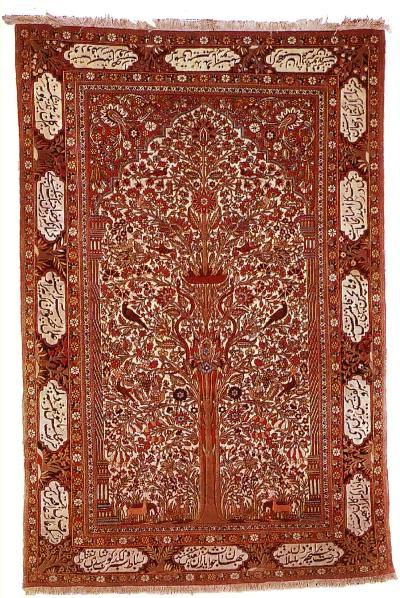

A Kashan

Mohtashemi

Woven at the end of the 19th Century.

Shows the tree of life and adorned round the borders with verses of Hafez.

Mohtashemi was a renowned weaver producing the best of Kashans.

|

| |

| |

Mesopotamia 9000 - 500 B.C

Early Farming Communities 9000-5000

| 9000 |

|

Beginning cultivation of wild wheat and

barley and domestication of dogs and sheep; inaugurating of change

from food gathering to food producing culture - Karim Shahir in

Zagros foothills. |

| 7000 |

|

At Jarmo, oldest known permanent

settlement: crude mud houses, wheat grown from seed, herds of

goats, sheep, and pigs. |

| 6000 |

Migration of northern farmers settle in

region from Babylon to Persian Gulf. |

Hassuna culture introduces irrigation,

fine pottery, permanent dwellings; dominates culture for 1000

years, develops tradefrom Persian Gulf to Mediterranean. |

Pre-Sumerians 5000-3500

| 5000 |

|

Ubaidians develop first divisions of

labor, mud brick villages, first religious shrines. Small temple

at Eridu - earliest example of an offering table and niche for

cult object. |

| 4500 |

|

|

| 4000 |

Semitic nomads from Syria and Arabian

peninsula invade southern Mesopotamia, intermingle with Ubaidian

population |

Temple at Tepe Gawra built

- setting style for later examples. |

Sumerians 3500-1900

| 3500 |

Sumerians settle on banks of Euphrates |

Temple at Eridu - zigguratprototype |

|

| 3000 |

Democratic assemblies give way to

kingships, evolve into hereditary monarchies. |

|

|

Kish - leading Sumerian city |

Introduction of pictographs to keep

administrative records.

3-D statues, e.g. Warka head.

White Temple - ziggurat traditional design.

Temple at Tell Uqair - mosaic decorations.

cuneiform land sales formal contracts.

Eridu and Kish - simple palaces.

"Standard of Ur" - war-peace plaque, religious

statues, gold and silver artifacts buried in tombs of Ur.

Sumerians of Abu Salabikh - first poetry. |

| 2750 |

|

|

Gilgamesh, hero of Sumerian legends,

reigns as king of Erech |

| 2500 |

Lugalannemudu of Abab unites city states

which vie for domination for 200 years. |

|

| 2250 |

Ur-Nammu founds Ur's 3rd. dynasty;

dedicates ziggurat at Ur moon-god Nanna, sets up early law

code. |

Gudea, Prince of Lagsh, art and lit

patron,magnificant statues produced in his honor. |

| 2000 |

Elamites attack and destroy Ur. |

Babylonians and Assyrians 1900-500

| 1900 |

Amorites from Syrian desert conquer

Sumer. |

|

| 1800 |

Hammurabi asccends Babylonian throne. |

|

| 1700 |

Hammurabi brings most

of Mesopotamia under his control. |

Hammurabi introduces law code. |

| 1600 |

Hittite invasion from Turkey ends

Hammurabi's dynasty. |

|

| 1500 |

Assyria conquered by Hurrians from

Anatolia. |

Bas-relief of baked brick appears as

dominant art form - Karaindash Temple. |

| 1400 |

Kurigalzu assumes Babylonian throne |

|

| 1200 |

Nebuchadrezzar I expels Elamites. |

|

| 1100 |

King Tiglath-Pileser I

leads Assyria to new era of power. |

Iron, introduced originally by

Hittites, is used extensively in Assyria for tools and

weapons. |

| 1000 |

Assyrian empire shattered by Aramaean

and Zagros tribes. 150 Assyrian decline halted by Adadnirari

II. |

| 900 |

|

Assurnasirpal II builds magnificent

new capital, Calah, replacing old capital of Assur, present

day Nimrud. |

| 800 |

Tiglath-Pileser II creates great

empire extending from the Persian Gulf to the borders of

Egypt. |

Sargon II builds new capitol at

Dur-Sharrukin |

| 700 |

Assurbanipal extends empire from Nile

to Caucasus Mountains. Chaldeans and Iranian Medes overrun

Assyria - Neo-Babylonian empire. |

Sennacherib's son, Esaraddon, rebuilds

Babylon. |

| 600 |

Nebuchadrezzar II rules Neo-Babylonian

empire. Razes Jerusalem, takes Jews into captivity in Babylon. |

Builds "Tower of Babel,"

temple to Marduk |

| 500 |

Cyrus the Great, Persian warrior and

statesman, conquers Babylon. |

|

Tabriz, Constitution House

constructed in 1312 (1933)

Tabriz, Constitution House

constructed in 1312 (1933)

Hamadan, Ganjnameh, inscriptions on Alvand

mountain

two tablets on granit, second tablet:

A great God is Ahuramazda, the greatest of

the God,

who created this earth, who created that

heaven,

who created man, who created happiness for

man,

who made Xerxes King, the one King of many

Kings, the one Lord of many Lords,

I am Xerxes,

the greath King, King of Kings,

the King of countries having many men, the

King in this great earth far and wide,

the son of Darius the King an Achaemenian.

Hamadan, Ganjnameh, inscriptions on Alvand

mountain

two tablets on granit, second tablet:

A great God is Ahuramazda, the greatest of

the God,

who created this earth, who created that

heaven,

who created man, who created happiness for

man,

who made Xerxes King, the one King of many

Kings, the one Lord of many Lords,

I am Xerxes,

the greath King, King of Kings,

the King of countries having many men, the

King in this great earth far and wide,

the son of Darius the King an Achaemenian.

Ramsar

Ramsar

Tus, Khorasan

Mausoleum of Ferdowsi

Tus, Khorasan

Mausoleum of Ferdowsi

Damavand (5671 m.)

The highest summit in Iran

Damavand (5671 m.)

The highest summit in Iran

Shahyad Tower, Tehran

Shahyad tower with museum is built in

1971 in Shahyad square on 50,000 sqm.

The height of this tower is 45 m.

Shahyad Tower, Tehran

Shahyad tower with museum is built in

1971 in Shahyad square on 50,000 sqm.

The height of this tower is 45 m.

Si-o-Seh Pol, Esfahan

Si-o-Seh Pol or Pol-e-Allahverdi Khan over

Zayandeh-Rud.

It consists of 33 arches and was

constructed with bricks (300 m. long & 14 m. wide) in 1602 A.D.

by the order of Shah Abbas I and by

Allahverdi Khan.

Si-o-Seh Pol, Esfahan

Si-o-Seh Pol or Pol-e-Allahverdi Khan over

Zayandeh-Rud.

It consists of 33 arches and was

constructed with bricks (300 m. long & 14 m. wide) in 1602 A.D.

by the order of Shah Abbas I and by

Allahverdi Khan.

Khaju Bridge, Esfahan

Khaju bridge was constructed over

Zayandeh-Rud, by the order of Shah Abbas II (1650 A.D.)

Khaju Bridge, Esfahan

Khaju bridge was constructed over

Zayandeh-Rud, by the order of Shah Abbas II (1650 A.D.)

Mausoleum of Hafez, Shiraz

Khajeh Shamseddin Mohammad, Hafez-e Shirazi

( 1300-1389 A.D. )

Mausoleum of Hafez, Shiraz

Khajeh Shamseddin Mohammad, Hafez-e Shirazi

( 1300-1389 A.D. )

Eram Garden, Shiraz

Eram (=Paradise) garden is a typical late

Qajar palace

Eram Garden, Shiraz

Eram (=Paradise) garden is a typical late

Qajar palace

Nagsh-e Rostam, Mausoleum of Cyros

Nagsh-e Rostam, Mausoleum of Cyros

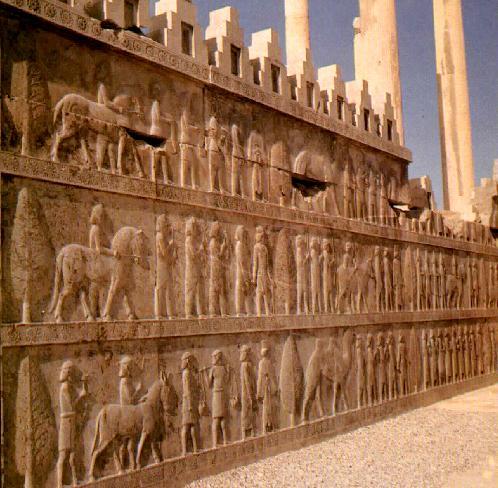

Persepolis

The site's Islamic name is Takht-e Jamishid,

"The thron of Jamshid".

The ancient name is "Parsa",

"Pars's Town",

was built during the reign of Darius by his

order in 514 B.C.

Persepolis

The site's Islamic name is Takht-e Jamishid,

"The thron of Jamshid".

The ancient name is "Parsa",

"Pars's Town",

was built during the reign of Darius by his

order in 514 B.C.

Falak-ol Aflak Fortress, Khorram Abad

The eight-towered fortress covers an area

of 5300 m², and the height about 40 m. above the

surrounding street level.

The original building of this fortress

dates back to the Sasanian period. Recorded sources

refer to it as Shapur-Khast or Sabr-Khast

fortress, Dezbaz, Khorram-Abad fortress,

and ultimately Falak-ol-Aflak fortress.

Falak-ol Aflak Fortress, Khorram Abad

The eight-towered fortress covers an area

of 5300 m², and the height about 40 m. above the

surrounding street level.

The original building of this fortress

dates back to the Sasanian period. Recorded sources

refer to it as Shapur-Khast or Sabr-Khast

fortress, Dezbaz, Khorram-Abad fortress,

and ultimately Falak-ol-Aflak fortress.

Shush (Susa)

Occupied for at least 6000 years from

prehistoric times.

The castle overlooking the Achaemenian

palaces was built some 90 years ago.

Shush (Susa)

Occupied for at least 6000 years from

prehistoric times.

The castle overlooking the Achaemenian

palaces was built some 90 years ago.

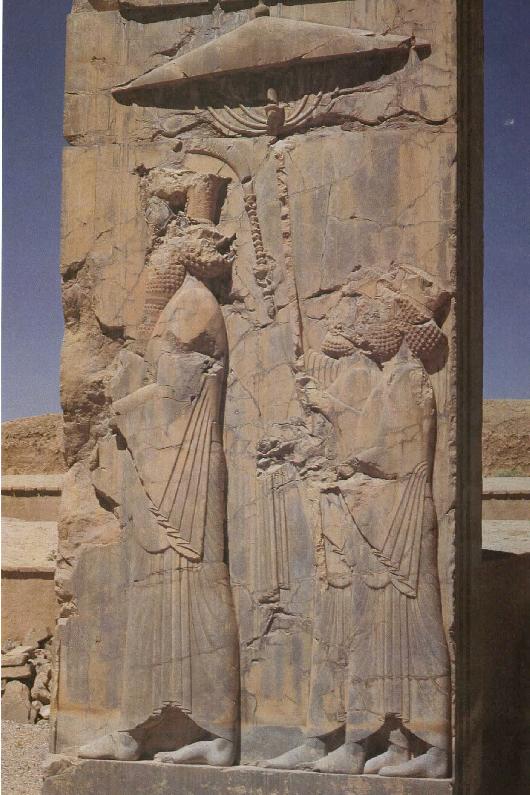

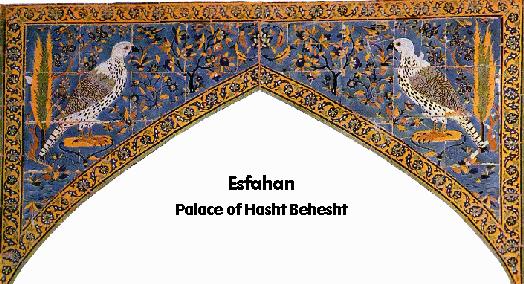

Tagh-e Bostan, Kermanshahan

The bas-relief on the right shows the

investiture of Ardeshir II (379 A.D.),

the King receives from God Hormozd a

ribbon-decked ring,

the symbol of Royal power,

to his right God Mithra holds a bunch of

sacred branches,

a ritual instrument in use since the Median

period.

Tagh-e Bostan, Kermanshahan

The bas-relief on the right shows the

investiture of Ardeshir II (379 A.D.),

the King receives from God Hormozd a

ribbon-decked ring,

the symbol of Royal power,

to his right God Mithra holds a bunch of

sacred branches,

a ritual instrument in use since the Median

period.

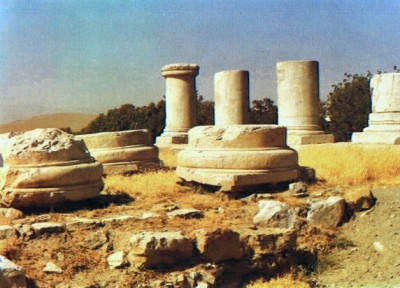

Anahita Temple

This temple attributed to the Parthian

period (200 B.C.)

Anahita Temple

This temple attributed to the Parthian

period (200 B.C.)

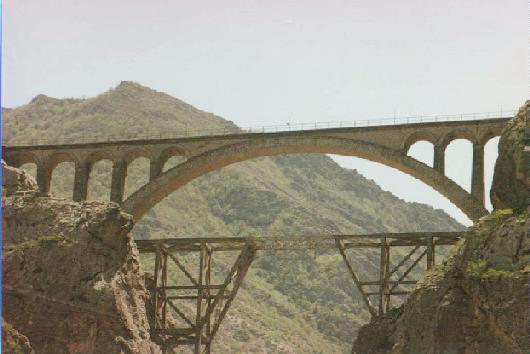

White Bridge, Ahvaz

White Bridge over Karun

500 m. long & 9 m. wide, was

built in 1937

White Bridge, Ahvaz

White Bridge over Karun

500 m. long & 9 m. wide, was

built in 1937

Bandar Abbas

Bandar Abbas

Bam, Kerman

The abandoned city, the forgotten fortress.

It was residential till 150 years ago and

there is no information about the exact date of the construction.

Bam, Kerman

The abandoned city, the forgotten fortress.

It was residential till 150 years ago and

there is no information about the exact date of the construction.

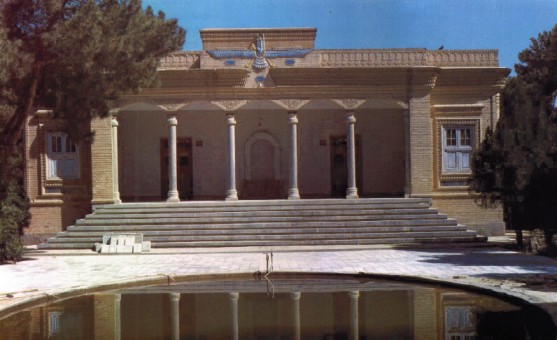

Yazd

Fire temple of Zoroastrians

Yazd

Fire temple of Zoroastrians

.............

.............